It is estimated that over 15 million people were displaced during the Partition of the Indian subcontinent and two million lost their lives in the ensuing communal violence.

This feature covers 42 years from 1906 to 1948, an astonishingly short period of time, during which the freedom movement emerged and subsequently achieved the creation of a separate Muslim state under the dynamic leadership of Mohammad Ali Jinnah – the Quaid-i-Azam – the monumental founder of this nation.

As the nation marks its 70th year, Pakistan’s story becomes your story.

TOWARDS THE FUTURE

DECEMBER 25, 1947

MR JINNAH’S LAST BIRTHDAY

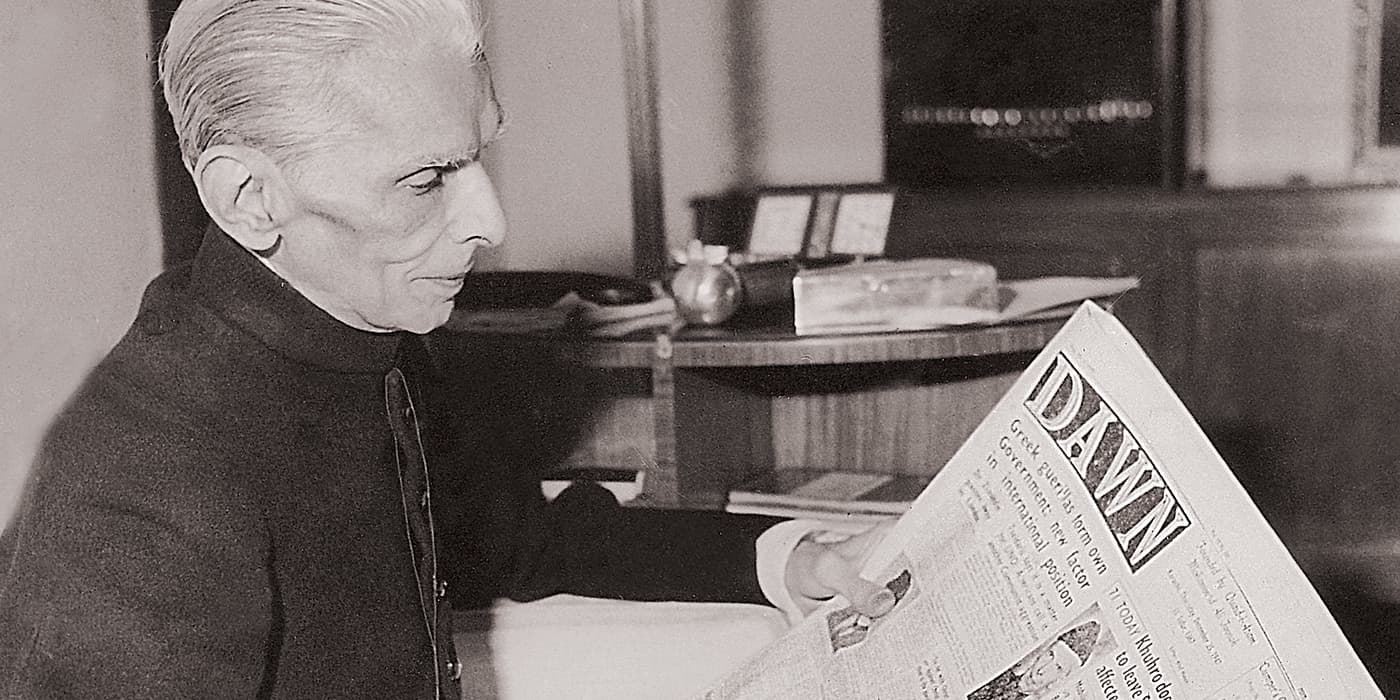

In the photograph above, courtesy Dawn/White Star Archives, Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah reads Dawn on his 71st birthday.

Mr Jinnah’s first birthday in Pakistan on December 25, 1947, is tragically his last one too. The morning starts when a smal delegation of journalists from Dawn Karachi, led by the editor, Altaf Husain, calls on him to express their best wishes. They find him reading the morning’s edition of Dawn.

As he reminisces about the heady days when Dawn is founded in Delhi, he expresses his satisfaction that the title and the ethos of Dawn are preserved and are prospering in Karachi.

And then something unusual happens. Never in his career has Mr Jinnah ever endorsed what today we would consider to be a ‘product’ or ‘brand’. And yet, at the behest of his colleagues, he picks up the copy of Dawn at his side and agrees to be photographed reading it.

The newspaper item on the front page congratulates Mr Jinnah on his 71st birthday, and there is a trace of a whimsical smile on his lips. He has come a long way from when he founded Dawn Weekly in October 1941. Those were days of hope; six years later, Dawn, published by Pakistan Herald Limited Karachi, is a living reality.

Later, Mr Jinnah attends the official reception at Governor-General House. He leaves early to attend a private birthday party given by his colleague, Sir Ghulam Hussain Hidayatullah.

As the Commander of the Sind Women’s National Guard, Pasha Haroon sings a birthday poem written for him by a poet in Lahore; he is visibly embarrassed and keeps knotting the napkin placed before him on the table. The words of the poem are: Millat kay liye aaj ghaneemat hai tera dumm, Aey Quaid-i-Azam/Sheeraza-e-Millat ko kiya tu ne faraham, aey Quaid-i-Azam. (Your breath alone is sufficient for the nation, oh Quaid-i-Azam/ You alone have been the binding force for the nation, oh Quaid-i-Azam.)

Nine months later, on September 11, 1948, Mr Jinnah surrenders to a prolonged bout of tuberculosis, an illness that afflicts him over the last decade of his life, and is kept a secret. The next day, Dawn pronounces “The Quaid-i-Azam is dead. Long live Pakistan!”

On the same day, Indian troops under the guise of police action, march into the Princely State of Hyderabad, and annex the state to India.

THE QUAID-I-AZAM 1947

THE LEGACY ENDURES

This photo, which appears on the cover of the January 5, 1948 edition of Life magazine, is part of a series taken by Margaret Bourke-White for the magazine.

Today, as Pakistanis celebrate the 70th year of their country’s existence, it is worthwhile to ponder on the legacy of Mr Jinnah, the man who founded what in 1947 is the world’s largest Muslim state.

An uncompromising adherence to the rule of law, freedom of speech and conscience, social justice and equality for all citizens, are the essence of his legacy; a legacy he wants the nation of Pakistan to uphold in the future. Although governance and law-making are the sole prerogative of the people’s elected representatives, as long ago as 1919, he tells the Imperial Legislative Council that “no man should lose his liberty or be deprived of his liberty without a judicial trial in accordance with the accepted rules of evidence and procedure.”

Although Mr Jinnah repeatedly avers that Islam has taught us “equality, justice and fair play”, he makes it clear that Pakistan will not be a theocratic state.

On August 11, 1947, in a historic reiteration of his political creed, he tells the Constituent Assembly: “You are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to your mosques or any other place of worship in this state of Pakistan. You may belong to any religion or caste or creed – that has nothing to do with the business of the state.”

Speaking on the topic of bribery and corruption, Mr Jinnah calls them “a poison” and declares: “We must put that down with an iron hand, and I hope that you will take adequate measures as soon as it is possible for this Assembly to do so.”

DELHI AUGUST 1947

A LONG WAIT TO FREEDOM

As thousands of Muslims seek refuge in this camp praying for a quick escape to Pakistan, thousands of Hindu and Sikh refugees from the Punjab pour into the city. An atmosphere of fear permeates, as anti-Muslim pogroms rock this historical stronghold of Indo-Islamic culture and politics.

Jawaharlal Nehru, the Indian Prime Minister, estimates that there are only 1,000 casualties in the city; other sources claim this figure is 20 times higher. Historian Gyanendra Pandey’s recent account of the Delhi violence puts the figure of Muslim casualties between 20,000 and 25,000.

Regardless of the number of casualties, thousands of Muslims are driven to refugee camps and historic sites in Delhi, such as the Purana Qila, Idgah and Nizamuddin, are transformed into refugee camps.

At the culmination of the tensions, 330,000 Muslims are forced to flee to Pakistan. The 1951 Census registers a drop in the Muslim population in the city from 33.22% in 1941 to 9.8% in 1951.

An estimated 15 million people from all sides will have crossed the borders to their chosen homeland as a result of Partition.

THE PRINCELY STATES

DHAKA MARCH 1948

THE SUPREME COMMANDER VISITS

This is Mr Jinnah’s last trip to Dhaka; had he lived beyond September 1948, he would certainly have made many more visits to the capital of East Pakistan.

Although the historic founding of the All-India Muslim League takes place in Dhaka in 1906, it is Calcutta (which Mr Jinnah frequently visits) that is the centre of politics in Bengal under British rule; it is only after Partition that Dhaka becomes the political hub of the Muslim majority in Bengal.

Khawaja Nazimuddin is the Chief Minister of East Bengal. At this time, political elements are stirring up issues of whether Bengali rather than Urdu should be the state language, thereby inflaming provincial sentiments among people. Mr Jinnah has come to Dhaka to clarify matters.

In a mammoth public meeting held in Dhaka on March 21, 1948, he declares that “having failed to prevent the establishment of Pakistan… the enemies of Pakistan have turned their attention to disrupting the state by creating a split among the Muslims of Pakistan. These attempts have taken the shape principally of encouraging provincialism. If you want to build up yourself into a nation, for God’s sake give up this provincialism.”

A few days later on March 24, speaking at the annual convocation of Dhaka University, Mr Jinnah says that people could choose to adopt the provincial language of their choice, but there could only be one lingua franca for the whole of Pakistan and that language should be Urdu.

General Ayub Khan becomes the second president of Pakistan after a military coup in 1958. He is forced to resign as president in 1969 after a popular uprising in East Pakistan and some other parts of the country.

As a consequence of his military rule, East Pakistan and its capital Dhaka are to be permanently lost to Pakistan a mere thirteen years later.

GILGIT & KASHMIR 1947

A PARTIAL VICTORY

November 1, 1947 is the day when Gilgit, Hunza and Baltistan accede to Pakistan.

Astore, Gilgit, Hunza and Nagar are part of territories conquered by the Dogra Maharajas. Their grip is tenuous and in 1889 the British create the Gilgit Agency as a means of turning the region into a buffer against the Russians. Then in 1935, the British lease the Gilgit Agency for a period of sixty years from Maharaja Hari Singh.

In 1947, Major William Brown, the Assistant Political Agent in Chilas, is informed that Lord Mountbatten has ordered that the 1935 lease of the Gilgit Agency (it still has 49 years to run) be terminated. Gilgit Agency, despite its 99% Muslim population, is to be allotted to the rule of Maharaja Hari Singh.

Meanwhile, stories of communal violence between Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims in the Punjab reach Gilgit, inflaming passions there. On October 26, 1947, the Maharaja signs the Instrument of Accession and joins India. (The signed document has never been seen.)

Sensing the discontent, Major Brown mutinies on November 1, 1947. He overthrows the governor, establishes a provisional government in Gilgit and telegraphs the chief minister of the NWFP asking Pakistan to take over. According to the leading historian Ahmed Hasan Dani, despite the lack of public participation in the rebellion, pro-Pakistan sentiments are strong amongst civilians.

Upon hearing of Maharaja Hari Singh’s accession to India, these tribesmen wait for Bacha Gul to lead them into battle in Kashmir. They reach the outskirts of Srinagar before they are pushed back to the upper reaches of what constitutes today’s Azad Kashmir.

Resistance in Poonch starts over issues related to taxation, but soon turns into an armed uprising when a public meeting is fired upon by Kashmir state forces. Two days later, the chief minister of the NWFP organises a guerrilla force to attack the Maharaja’s forces in the Dheer Kot camp. According to Australian historian Christopher Snedden, it is the Muslims in the Poonch region of Kashmir who instigate the uprising and not Pakhtoon tribesmen invading from Pakistan, as India consistently maintains.

India’s case on Kashmir is built upon a version of events that asserts that India’s military intervention is in response to a tribal invasion supported by Pakistan. On January 1, 1948, India takes the issue to the UN Security Council. The Security Council pass a resolution calling for Pakistan to withdraw from Jammu and Kashmir and for India to reduce its forces to a minimum level, following which a plebiscite is to be held to ascertain the people’s wishes.

Dispute erupts over the implementation mechanism because of which the Kashmir problem remains unresolved to this day.

SWAT, NOVEMBER 24, 1947

THE WALI ASSENTS

Swat owes its status as a ‘state’ to the decline of the Sikh and Afghan empires. When the British take over Peshawar in 1849, Swat is mainly inhabited by Yusufzai Pathans. The same year, the tribal jirga elects Syed Akbar Shah as king of Swat – although real power in Swat lies with the Akhund, a religious leader known as Saidu Baba.

Saidu Baba dies in 1887 and Swat lapses into factional fighting between his sons and his grandsons.

Finally, in 1917 the jirga appoints Miangul Abdul Wadud, one of the Akhund’s grandsons as king. Although Miangul Abdul Wadud controls most of Swat by 1923, the Government of India does not formally recognise him as the ruler. Instead, in 1926 the British grant him the title of Wali, an honorific religious title – because only the King Emperor in England has the right to the title of king.

Irrespective of the British position, the Wali of Swat is the only elected ruler of a Princely State, by virtue of the jirga.

In 1931, Swat has an area of 18,000 square miles and a population of 216,000. The state is predominantly Muslim, but with a small Hindu presence. Swat’s accession to Pakistan is complicated by its occupation of Kalam shortly before 1947, which was also claimed by Chitral and Dir.

Although Pakistan refuses to recognise the occupation and tries to persuade Swat to revert to the status quo, the Wali, hoping to garner Pakistan’s support of Swat’s claim to Kalam, is eager to accede to Pakistan. Miangul Jahanzeb, the last Wali notes that “with the creation of Pakistan, we immediately joined the new state. We were very patriotic… I talked to the political agent Nawab Shaikh Mehboob Ali over the telephone and told him we were going to sign the Instrument of Accession.”

The Wali executes the Instrument of Accession on November 24, 1947.

BAHAWALPUR, OCTOBER 3, 1947

THE AMIR ACQUIESCES

The Nawabs of Bahawalpur claim descent from the Abbasid caliphs of Baghdad – and in this way distinguish themselves from the other ruling princes of India. They receive their first grant of land from Emperor Nadir Shah and subsequently come under the suzerainty of Ahmed Shah Durrani. When the Durrani Empire crumbles, they assume independence. However, the rise of Sikh power prompts them to sign a treaty with the East India Company in 1833, accepting the paramountcy of the Company.

Nawab Sadiq Abbasi becomes ruler of Bahawalpur at the age of 18 months, and until 1924, the state is ruled under the regency of his eldest sister.

In 1941, Bahawalpur has an area of 17,494 square miles and a population of over 1.3 million subjects. In 1947, the Nawab is in poor health; he is in England and is advised by his doctors to remain there. This is a crucial moment for Bahawalpur; the state has contiguous borders with India and Pakistan and can choose to accede to either country. Yet, no decision can be taken in the Nawab’s absence. Sir Penderel Moon, the historian and also Public Works Minister in the Bahawalpur Government, notes: “Jinnah, unlike the Congress leaders, was not hostile to the ruling princes and had no plans for sweeping them away or curtailing their powers.”

In April 1947, Mushtaq Ahmed Gurmani, a Unionist minister from the Punjab is appointed prime minister of the state. As the date for the Transfer of Power approaches, rumours circulate that Bahawalpur may accede to India.

On August 15, 1947, Nawab Sadiq Abbasi declares himself Amir (independent ruler), announcing his willingness to enable Pakistan and Bahawalpur “to arrive at a satisfactory constitutional arrangement.” The Government of Pakistan, alarmed by Bahawalpur’s intentions, moves to ensure the state’s accession to Pakistan. Negotiations are stymied when the Nawab decides to return to England.

Despite rumours that Mr Gurmani is planning Bahawalpur’s accession to India, he does not oppose the accession; the only complication is the signature of the Amir, which he gives on October 3, 1947.

Nawab Sadiq Abbasi is the last reigning ruler before Bahawalpur’s accession to Pakistan. He follows in the tradition of the Abbasid caliphs by travelling through his state in disguise in order to better understand what is required for effective governance.

He builds schools, hospitals, roads, bridges and an agricultural canal system to create more arable land in the desert. He possesses one of the finest stamp collections in the world and owns one of the largest collections of custom-made Rolls-Royces and Bentleys. He is known for his love of fine art objects and of fine food.

KHAIRPUR, OCTOBER 3, 1947

WELCOMING THE BOY PRINCE

The Talpur rule in Sindh begins in 1783, when Mir Fateh Ali Khan Talpur of Hyderabad declares himself Rais of Sindh, having obtained a farman to this effect from the king, Shah Zaman Durrani. Mir Fateh Ali Khan Talpur’s nephew, Mir Suhrab Khan, settles in Rohri and establishes the foundations of the state of Khairpur.

Recognising the rising power of the East India Company, the Mir offers Khairpur’s assistance to the British during the First Afghan War. This is an astute move, as the continued existence of Khairpur is largely a consequence of this policy.

On July 24, 1947, the British depose the reigning Mir Faiz Muhammad Khan II due to his poor health and appoint his son, Mir George Ali Murad Khan Talpur II, as the ruling Mir. Because he is a minor, a Board of Regency is created with a rotating chairmanship made up of close male relatives of the Mir – Mir Ghulam Hussain Khan Talpur is one such regent.

In the early 1940s, Khairpur covers an area of 6,050 square miles, and its population is estimated to be in the region of 300,000, sixteen percent of whom are non-Muslims.

A large portion of the Lahore-Karachi railway track is within the State and this explains why the Government of Pakistan considers its integration important.

On August 4, 1947, the Khairpur government issues a notification that August 15, 1947 will be celebrated as Khairpur’s Independence Day. However, repeated efforts by the Government of Pakistan finally persuade Mir Ghulam Hussain Khan Talpur to sign the Instrument of Accession on behalf of the boy prince on October 3, 1947 – the same day as Bahawalpur accedes.

Hence, on the same day, Pakistan gains two valuable Princely States, not only significant in terms of land mass, but in terms of agricultural land, nascent industries and strategic value.

BUILDING THE NATION

LAHORE 1946-47

AN ENGAGEMENT WITH THE PIONEERS

Students, particularly from the Punjab, play a pivotal role in the 1945 general elections.

The elections are vital for the Muslim League because failure to win the Muslim seats will mean that further discussion on the demand for Pakistan will be dismissed by the Congress and the British Government. Consequently, the Muslim League moves to mobilise Muslim students.

Nawabzada Liaquat Ali Khan exhorts the students of the Aligarh Muslim University to give up their studies for a period of time and campaign for the Muslim League. A training camp is set up on campus and students are given training courses before they are sent to various parts of the province. An election office opens in Islamia College in Lahore and the Punjab Muslim Students’ Federation establish an election board to spread the Muslim League’s message.

Two hundred students are deputed to tour 20 constituencies covering 400 villages. By the end of the campaign, the Muslim League says 60,000 villages are visited by their student campaigners.

As a result of this massive student mobilisation, a remarkable victory is achieved by the Muslim League, obliterating the failure of the 1936-37 elections.

Sir Sikandar Hayat Khan dies in 1942. Determined to prevent any attempt by Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah to intervene in the politics of the Punjab, his successor, Malik Khizar Hayat Khan Tiwana, disregards the Jinnah-Sikandar pact of 1937.

When negotiations fail, Malik Khizar Hayat Khan Tiwana is expelled from the Muslim League. The 1945 elections confirm the Muslim League as the single largest party in the Punjab Legislature. Yet, the British Government does not call upon them to form the government; they ask Malik Khizar Hayat Khan Tiwana to cobble together a majority government through a coalition with the Hindu and Sikh members of the assembly.

This leads to a civil disobedience campaign in the Punjab and then mass agitation, when Muslim League leaders are arrested in January 1947. Undaunted, the women of the Muslim League defy the ban on demonstrations and court arrest. Eventually, the coalition government is paralysed, Malik Khizar Hayat Khan Tiwana resigns and governor rule is imposed.

The women, like the students, play a pivotal role in enabling the creation of Pakistan.

THE NATIONAL GUARD 1948

EMPOWERING WOMEN

The Sind Women’s National Guard is a small group of about 25 to 30 teenagers who wear white uniforms, learn first aid and self defence, and encourage citizens to vote.

This photograph is taken in 1947 and Zeenat Rashid is 18 years old. Her father, Haji Abdullah Haroon, passes away five years earlier. Her mother, Lady Nusrat Abdullah Haroon, continues to be a dominant figure in the Pakistan Movement. As a captain in the Sind Women’s National Guard, Zeenat Rashid gathers 35 school friends to form the caucus of Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah’s young women’s contingent.

She explains: “The Quaid-i-Azam said to us: ‘The women are standing shoulder to shoulder with the men. What are you young people doing?’” Zeenat Rashid’s answer to her hero was: “We are ready; what do you want us to do?”

Later, in an interview with Life magazine, she recounts that: “We were a symbol. Mr Jinnah wanted to show people that in Pakistan, women would do things. We didn’t cover our heads! What nonsense. We were a symbol of progress.”

Her grandest moment? It is 1947 and she is practising with the Sind Women’s National Guard, brandishing a lathi – it is then that Margaret Bourke-White captures these magical moments. The one above is part of a series of images in Life magazine’s cover story on Pakistan in January 1948.

A DEMOCRATIC PUNJAB 1937-47

FRIENDLY PERSUASION

After winning the general elections in the Punjab in 1937, Sir Sikandar, the leader of the Unionist Party in the Punjab, is faced with pressure from many of his Muslim parliamentary colleagues. Mindful of the need to maintain an equitable stance in a divided Punjabi political milieu, Sir Sikandar enters into negotiations with Mr Jinnah. As a consequence, the Jinnah-Sikandar Pact is signed.

The pact is essentially an arrangement whereby the Muslim League will represent the Muslims at the national level, while the Unionists will maintain a measure of independence at the provincial level.

Mr Jinnah’s ability to deal with various hues in the tapestry of the Punjab through democratic persuasion is reflected in the Muslim League’s ascension to power after 1947.

Mian Iftikharuddin is a scion of the Arain Mian family, custodians of Lahore’s Shalimar Gardens. He begins his political career in the Congress and rises to the presidency in the Punjab. In 1945, he joins the Muslim League. After Partition, he is elected as the first President of the Punjab Provincial Muslim League and Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah appoints him Minister for the Rehabilitation of Refugees.

In 1947, Mian Iftikharuddin founds the Pakistan Times; Faiz Ahmed Faiz is appointed Editor-In-Chief.

In 1949, Mian Iftikharuddin’s proposal for land reforms in the Punjab leads to a backlash from the feudal leadership within the Muslim League. In frustration, he resigns from his ministry and is expelled from the Muslim League in 1951.

After his death in 1962, Faiz Ahmed Faiz pays tribute to him with this couplet: Jo rukey tu koh-e-garan thay hum/ Jo chalay tu jaan say guzar gaye/ Raah-e-yaar hum ne qadam qadam/ Tujhay yaadgaar banaa diya (For when we stayed, we rose like mountains/ And when we strayed, we left life far behind/ Fellow traveller, every step that we ever took/ Became a memorial to your life).

It is a tribute to Mr Jinnah’s political sagacity that he can mobilise talents like Mian Iftikharuddin’s to work within his government in the Punjab.

KARACHI & DELHI 1947

A TRIUMPH AND A TRAGEDY

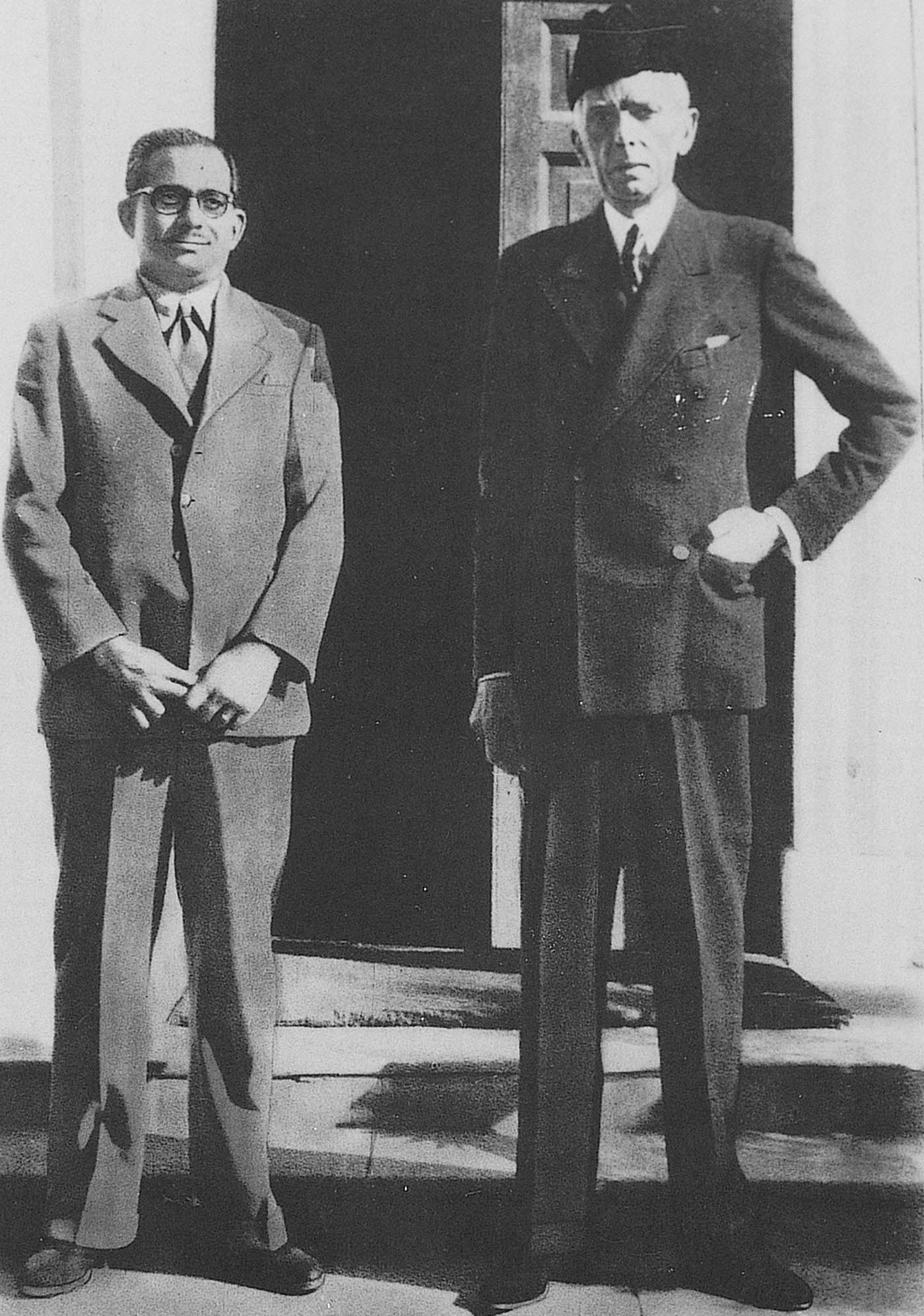

Dawn Delhi and Dawn Karachi are founded by Mr Jinnah. Mr Husain is first appointed editor of Dawn Delhi in 1945; his predecessor was Pothan Joseph. In August 1947, Jan Sangh demonstrators accuse Dawn Delhi journalists of firing at Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel’s procession. This is when Mr Jinnah asks for Mr Husain to be transferred to Karachi and assume the editorship of Dawn Karachi, which is published by the family of Mr Jinnah’s late friend Haji Abdullah Haroon. It is plain to him that Dawn Delhi will not survive the threats of the Jan Sangh. Dawn Delhi is burnt down on September 14, 1947. Despite this, Dawn Karachi continues to carry the inscription: ‘Published simultaneously from Delhi and Karachi’ on the masthead until October 21, 1947, when it is removed and Mr Jinnah accepts the reality that Dawn Delhi is no more.

The loss of Dawn Delhi is a tragedy for Mr Jinnah, for this was the paper he founded and nurtured in 1941 to carry forward the Muslim League’s message across undivided India. His triumph is the survival of Dawn Karachi.

To the right of Mr Jinnah is Pothan Joseph, the editor of Dawn Delhi. Behind Nawabzada Liaquat Ali Khan is Hamid Zuberi, who subsequently joins Dawn Karachi; to the left of Nawabzada Liaquat Ali Khan is Mahmud Husain, GM, Dawn Delhi.

Mr Jinnah founds Dawn Delhi on October 19, 1941, to represent the views of Indian Muslims. The offices are housed in an old building in the Daryaganj area of Delhi. The furniture is modest, the staff minimal and the pay low. Yet, everyone is full of zeal. Mr Jinnah and his editors – Pothan Joseph and then Altaf Husain – inspire them with a strong spirit of nationalism as the newspaper fights for justice and fair play for the Muslims.

PIECING TOGETHER PAKISTAN

KARACHI 1948

THE ARCHITECT OF THE NATION

Mr Jinnah’s personal interest in selecting the national anthem is indicative of his painstaking attention to detail about everything that touches upon Pakistan’s future. (His earlier care in designing the national flag, with its broad white band representing the minorities, is further evidence of the importance he attributes to these matters.)

It is not known whether this is the musical score composed by Ahmed Ghulamali Chagla and selected in 1949. The lyrics are written as late as 1952 by Hafeez Jullundhri. In 1954, the anthem is officially adopted as Pakistan’s qaumi tarana.

As Governor-General, Mr Jinnah steers the nation’s policy, achieving significant results. He nominates Pakistan’s Federal Cabinet and in the absence of a constitution, amends and enforces the Government of India Act 1935. He reorganises the civil service and develops cordial relations with Pakistan’s neighbours and the West. On September 30, 1947, Pakistan becomes a member of the UN. Nawabzada Liaquat Ali Khan has an important role in these matters.

Critics state that the Jinnah-Liaquat relationship deteriorates during Mr Jinnah’s last days. Such conjecture fails to recognise the fact that Mr Jinnah never revoked his decision to nominate Nawabzada Liaquat Ali Khan as one of the three executors of his will – by no means a small matter for a person as particular as Mr Jinnah when it comes to his private matters.

For Mr Jinnah “the opening of the State Bank of Pakistan symbolises the sovereignty of our state in the financial sphere.”

As per the Pakistan Monetary System and Reserve Bank Order 1947, the Reserve Bank of India is to continue to be the currency and banking authority of Pakistan until September 30, 1948. Mindful of this date, Mr Jinnah performs the inauguration in advance of this deadline on July 1, 1948.

PESHAWAR 1945-48

CROSSING THE LAST FRONTIER

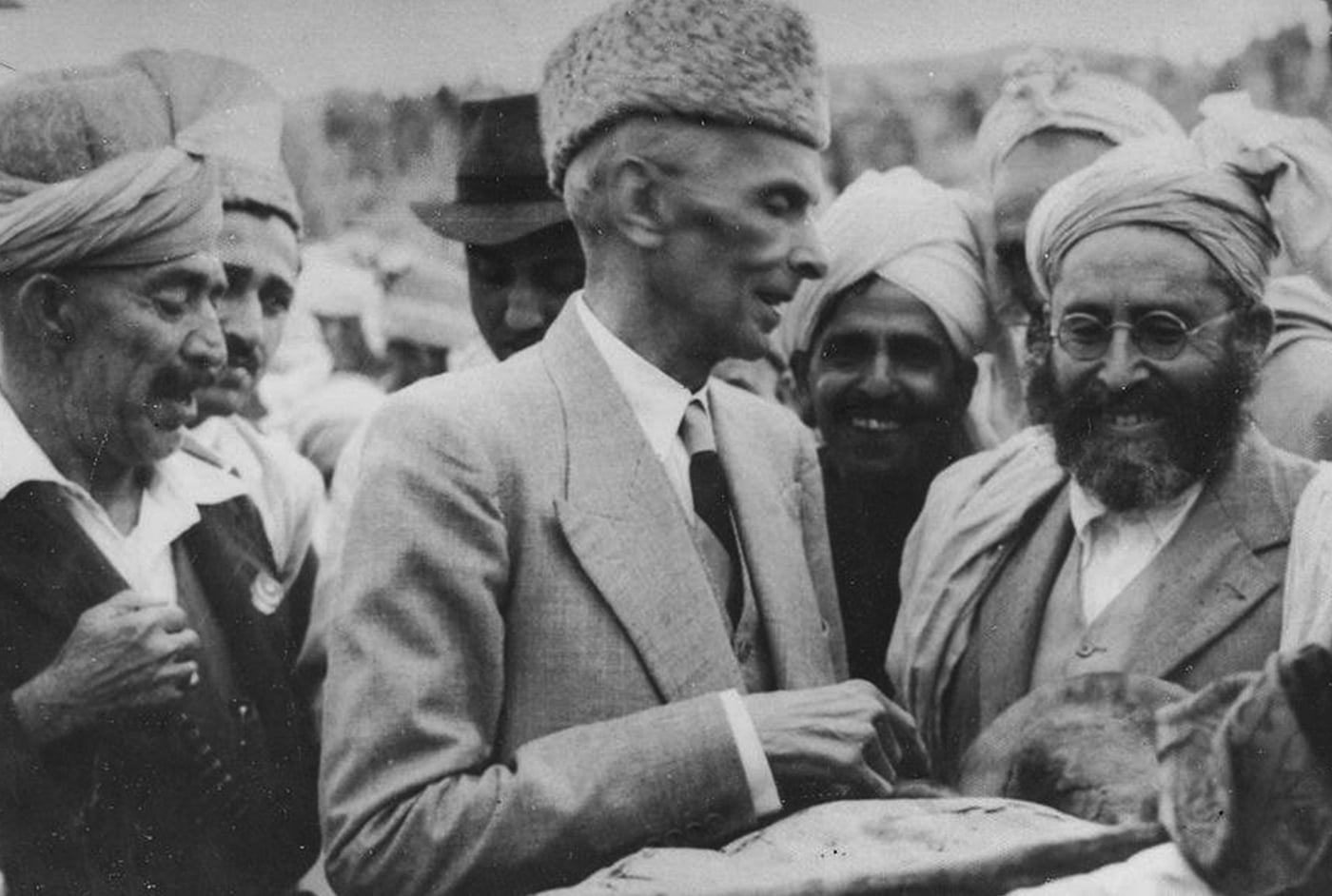

In this second visit to the NWFP, Mr Jinnah addresses rallies in Peshawar, Mardan and in the tribal areas. Since 1937, a Congress-Redshirt government is in power in the NWFP. The Muslim League’s popularity is surging amidst Muslim dissatisfaction that although Hindus and Sikhs account for only seven percent of the representation in the Assembly, the British Government has accorded them a disproportionate 24% of the seats.

However, the problems in the NWFP are not communal; they arise from a clash between the Hindu-financed Congress-Redshirt government and the Muslim League, and are further complicated by the tribes who, broadly speaking, are in sympathy with the Muslim League.

In February 1947, the Muslim League launches a civil disobedience movement against the Congress-Redshirt government, which rapidly gains momentum. As Partition approaches, the Congress agree to the British proposal to hold a referendum on the future of the NWFP. In June, Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan announces the boycott of the referendum and calls for the establishment of an independent state for Pakhtoons called ‘Pathanistan’. The stock of the Congress-Redshirt government in the NWFP plummets and the momentum swings to the Muslim League.

This is Mr Jinnah’s third visit to the NWFP; he spends 10 days touring the province from Khyber to Gomal. This special equation between Mr Jinnah and the tribesmen is a major factor in the Muslim League’s landslide victory in the 1947 referendum on the decision to join Pakistan.

Mr Jinnah has secured the Frontier for Pakistan.

LAHORE 1947

RECLAIMING THE HEARTLAND

The violence that mars Partition is a period of great personal anguish for Mr Jinnah. Yet, his clarity of thought is unimpaired. He states: “Some people might think that the acceptance of the June 3, 1947 Plan was a mistake on the part of the Muslim League. I would like to tell them that the consequences of any other alternative would have been too disastrous to imagine…”

A man who has never compromised on his essential beliefs, he continues with conviction: “The tenets of Islam enjoin on every Musalman to give protection to his neighbours and to the minorities regardless of caste and creed. Despite the treatment which is being meted out to the Muslim minorities in India, we must make it a matter of our prestige and honour to safeguard the lives of the minority communities…”

Despite Mr Jinnah’s campaign efforts, the Muslim League lose these elections.

In Punjab, the Unionists, led by Sir Sikandar Hayat, win 67 of the 175 seats; the Congress 18 seats and the Akali Dal 10 seats. Although many Muslim Unionists are ardent supporters of the Muslim League, the Unionist party in Punjab formally constitutes a distinct entity and the Muslim vote is divided.

The election loss galvanises the Muslim League to redouble their efforts in Punjab and turn themselves into a credible alternative to the Unionists and reclaim Punjab. They achieve this in the 1945 elections.

BALOCHISTAN 1943-48

WINNING HEARTS AND MINDS

Mr Isa, a prominent leader of the Pakistan Movement, plays a pivotal role in facilitating Mr Jinnah’s visit to Balochistan and his meetings with Baloch leaders. This is one of several visits Mr Jinnah makes to Balochistan.

During Mr Jinnah’s stay in Sibi, he schedules three meetings with the Khan of Kalat to discuss matters related to the accession of Kalat.

The last meeting is scheduled for February 14 in Harboi, the Khan of Kalat’s mountain estate. The meeting is cancelled due to the sudden ‘illness’ of the Khan.

Balochistan consists of British Balochistan, the state of Kalat, Lasbela, Kharan and Makran; the latter three are placed under Kalat’s rule as fiduciary states by the British. Three months before Partition, Mr Jinnah is in negotiations with the British on the future status of Kalat and of British Balochistan. After several meetings between Lord Mountbatten, Mr Jinnah and the Khan, a Standstill Agreement between Pakistan and Kalat is announced on August 11, 1947, with a proviso that there will be further discussions with respect to an agreement on defence, external affairs and communications.

Mr Jinnah then undergoes a change of thinking. His view is that Kalat should sign the Instrument of Accession, just as the other Princely States have done, but the Khan and the Dar-ul-Awam Assembly resist.

By March 18, 1948, Lasbela, Kharan and Makran accede to Pakistan and on March 26, 1948, Pakistan’s Army moves into Jiwani, Pasni and Turbat.

On March 28, 1948, the Khan agrees to merge his now landlocked state with Pakistan. The agreement is backdated to August 15, 1947.

Despite the many disagreements along the way, Mr Jinnah’s efforts succeed in winning the hearts and minds that matter.

HOLOCAUST

1947

EXODUS

Immediately after Partition, massive population exchanges occur between India and Pakistan. Six-and-a-half million Muslims move from India to West Pakistan and 4.7 million Hindus and Sikhs from West Pakistan to India.

Only thirty-two miles separate Amritsar from Lahore. Hindus and Sikhs constitute about a third of Lahore’s population and in Amritsar, Muslims account for half of the city’s population. Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs have links in both cities; some have their homes in one and their businesses in the other. Then Partition intervenes and from August to November 1947 huge caravans of refugees from both cities join the mass exodus; Muslims are fleeing from East Punjab and Hindus and Sikhs from West Punjab.

This exodus is accompanied by unprecedented violence on both sides and is most tragically witnessed in the attacks on trains crammed with refugees, and the arrival of trainloads of corpses at both ends of the railway line. The violence destroys 4,000 houses in Lahore and most of the 6,000 houses in the Walled City are badly damaged. Amritsar is the worst affected city in Punjab, with almost 10,000 buildings burnt down.

Although in the second half of 1947 Sindh is still relatively free of communal violence, Hindus and Sikhs begin migrating to India. According to noted Sindh historian, Dr Hamida Khuhro, Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah “fully expected to retain the minority communities in Pakistan” and Ayub Khuhro, his Chief Minister in Sindh, declares the “Hindus to be an essential part of the society and economy of the province.”

Yet, events spin out of control as violence breaks out in Ajmer on December 6, 1947, and then in the Thar Desert, where Muslim casualties are high. On January 6, 1948, anti-Hindu riots break out in Karachi and the situation is aggravated when new arrivals from India forcefully take possession of houses in Karachi and Hyderabad that are still occupied by their Hindu owners.

In September 1947, according to estimates published by the Times of India, 12,000 non-Muslims leave Sindh for Mewar and other Princely States via Hyderabad (Sindh) and approximately 60,000 non-Muslims leave Karachi by rail, sea and air. In Bombay alone, 290,000 non-Muslims arrive on January 7, 1948 after leaving Karachi on August 15, 1947.

AUGUST 1947

A PUNJAB TORN ASUNDER

Sir Cyril Radcliffe arrives in India on July 8, 1947. His instructions are to draw up a boundary line between India and Pakistan by August 15, 1947. His objections to the short time frame are ignored. The problem is that Punjab’s population distribution is such that no boundary can divide Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims without massive disruption.

The Commission has four representatives; two from the Congress and two from the Muslim League. But the bitterness between the two sides means that the final decision is Sir Cyril’s alone.

As soon as the Commission announces the demarcation line on August 17, 1947, mass migration movements erupt, as Hindus and Sikhs in West Punjab move east, and Muslims in East Punjab move west.

Over the following days, the migrations assume staggering proportions and the violence on all sides of the communal spectrum is catastrophic, and estimates of the death toll vary between 200,000 and two million.

Mr Radcliffe leaves India immediately after completing the demarcation, destroying all his papers before departing.

In 1966, W.H. Auden, the celebrated English poet writes a poem on Mr Radcliffe’s Partition, evoking the difficulties of his task:

“Shut up in a lonely mansion, with police night and day/ Patrolling the gardens to keep assassins away,/ He got down to work, to the task of settling the fate/ Of millions. The maps at his disposal were out of date/ And the Census Returns almost certainly incorrect/ …But in seven weeks it was done, the frontiers decided,/ A continent for better or worse divided.”

Punjab was indeed torn asunder.

THE SOLE SPOKESMAN

KARACHI AUGUST 15 1947

ENTER THE GOVERNOR-GENERAL

“I, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, do solemnly affirm true faith and allegiance to the Constitution of Pakistan as by law established, and that I will be faithful to His Majesty King George VI, in the office of Governor-General of Pakistan.”

It is Friday, August 15, 1947 and as Mr Jinnah speaks these words, as enunciated in the Indian Independence Act, 1947, the culminating moment of his long struggle for Pakistan is at hand. The oath of office is administered by Mian Abdul Rashid, the Chief Justice of the Lahore High Court (Mian Abdul Rashid later becomes the first Chief Justice of Pakistan). A thirty-one gun salute follows immediately.

Next, the first Cabinet of Pakistan is sworn in. Nawabzada Liaquat Ali Khan is appointed as the first Prime Minister. Cabinet Ministers include I.I. Chundrigar (Trade & Commerce); Malik Ghulam Muhammad (Finance); Sardar Abdur Rab Nishtar (Communications); Raja Ghazanfar Ali Khan (Food, Agriculture & Health); Jogendra Nath Mandal (Law & Labour); and Mir Fazlur Rahman (Interior, Information & Education).

Following these ceremonies, Mr Jinnah, resplendent in a white sharkskin sherwani, walks towards the naval guard and acknowledges their salute. Although it is the month of August, the day’s heat dissipates under slightly overcast skies and the light incoming winds from the Arabian Sea.

Mr Jinnah walks down the steps of the cascading patio and on to the lawns of Government House, where dignitaries, diplomats, government functionaries and political veterans wait to congratulate him. On the outside perimeter, cheering crowds gather, intent on catching a glimpse of their Governor-General.

The last image of Mr Jinnah and Miss Fatima Jinnah on this historic day is of them waving from one of the balconies of Government House as the Pakistan flag flutters in the wind.

KARACHI AUGUST 1947

PAKISTAN ZINDABAD

The All-India Muslim League National Guard, founded in the United Provinces in 1931, is a quasi-military organisation associated with the Muslim League. The goal of the National Guard is to mobilise and inspire young Muslims with the values of tolerance, sacrifice and discipline. In 1934, the National Guard is given a further boost by Mr Jinnah and the organisation spreads across all the states of united India to activate participation in the Pakistan Movement.

The rally pictured here is met by a mammoth crowd raising the twin slogans of “Leke Rahenge Pakistan” and “Leke Rahenge Kashmir.” This rally in Karachi is part of an overall effort to mobilise all sections of the country in favour of Pakistan in the wake of Independence.

This photograph of Saeed Haroon was taken by Margaret Bourke-White and appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle in 1947 and subsequently as part of a series of images in Life magazine’s cover story on Pakistan in January 1948.

BOMBAY AUGUST 1947

THE SOLE SPOKESMAN

We are a few weeks before Mr Jinnah’s final departure for Karachi, where he will be sworn in as Pakistan’s first Governor General.

For the moment he is still able to enjoy the pleasures of his well-appointed home in Bombay.

A long journey has taken him from being the ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity to becoming the sole spokesman for the Muslims of undivided India. This remarkable transition in his political career is analysed in The Sole Spokesman, a groundbreaking work by Pakistani historian, Dr Ayesha Jalal.

Single-handedly Dr Jalal transforms the whole prism through which Mr Jinnah’s career is viewed after his return from a self-imposed exile in London, and her work is a source of inspiration for many subsequent historians in South Asia and abroad, including the former Indian foreign minister, Jaswant Singh.

Here, Dr Jalal explains the dynamics of the concept of the sole spokesman.

Mr Jinnah was representing a divided Muslim community that needed to speak with one voice in order to be effective in the negotiations to determine independent India’s constitutional future. So when Mr Jinnah spoke to the British and the Congress, he claimed to represent all Muslims – be it in Muslim majority provinces or in Muslim minority ones.

Earlier in his career, Mr Jinnah had been styled the “ambassador for Hindu-Muslim unity” by his political mentor in the Congress, Gopal Krishna Gokhale. Here, by contrast, Mr Jinnah himself claimed to be the sole spokesman of all Indian Muslims, a tactic that was intended to counter the Congress’s claim to speak on behalf of all Indians and paper over the cracks within the Indian Muslims. The remarkable corollary to this was that throughout his political career,

Mr Jinnah consistently championed minority rights. He demonstrated this aspect in his first address to the Pakistan Constituent Assembly in August 1947 and in subsequent statements in the post-independence period. There was a paradoxical side effect to Mr Jinnah’s claim to be the sole spokesman of the Muslims in India. The Congress used Mr Jinnah’s demand for Muslim self-determination to insist on similar rights for non-Muslims in the two main Muslim majority provinces of Bengal and Punjab.

Pressed by the Hindu Mahasabha, the Congress high command called for the partition of these two provinces in March 1947, turning Mr Jinnah’s idea of an undivided Punjab and undivided Bengal for the Muslim state of Pakistan on its head.

This is why, concludes Dr Jalal, “it is a mistake to confuse the demand for Pakistan with the truncated Pakistan that emerged after the partition of Bengal and Punjab.”

KARACHI AUGUST 14, 1947

THE QUAID ASSUMES POWER

Seated behind him on the podium is Lord Louis Mountbatten. Lady Edwina Mountbatten is seated beneath the podium on the left.

Three days earlier, on August 11, 1947, at the inaugural session of the Constituent Assembly in Karachi, Mr Jinnah delivers a landmark address, setting out some of the key components of his vision for Pakistan. On the subject of the freedom of religious expression he says: “You are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to your mosques or to any other place of worship in this state of Pakistan. You may belong to any religion or caste or creed, that has nothing to do with the business of the state… We are all equal citizens of one state.”

Now, Mr Jinnah prepares for the Dominion of Pakistan to assume power… Lord Mountbatten has returned to his seat after delivering his address to mark the transfer of power. In his speech Lord Mountbatten says: “I would like to express my tribute to Mr Jinnah. Our close personal contact and the mutual trust and understanding that have grown out of it are, I feel, the best omens for future good relations…”

Mr Jinnah, dressed in a white sharkskin sherwani, in measured extempore and with a few notes in his hand, replies: “Your Excellency, I thank His Majesty the King on behalf of the Pakistan Constituent Assembly and myself for his gracious message… Great responsibilities lie ahead… It will be our continuous effort to work for the welfare and well-being of all the communities in Pakistan…”

The next day, Mr Jinnah will be sworn in as Pakistan’s first Governor General by the Chief Justice of the Lahore High Court, Mian Abdul Rashid.

![Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah, Miss Fatima Jinnah, Lord Louis Mountbatten and Lady Edwina Mountbatten face jubilant crowds as they leave the Constituent Assembly. — Courtesy Directorate of Electronic Media and Publications [DEMP], Ministry of Information Broadcasting & National Heritage, Islamabad](https://i.dawn.com/primary/2017/07/5978757e3f397.jpg)

Mr Jinnah and Lord Mountbatten drive together to Government House in a gleaming Rolls-Royce. Later in the afternoon, Lord and Lady Mountbatten leave for Delhi to attend the independence celebrations in India.

DELHI JUNE 3, 1947

ONWARDS TO PARTITION

Earl Louis Mountbatten of Burma, the last viceroy of India is seated in his study at Viceroy House. To the right are Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah, Nawabzada Liaquat Ali Khan and Sardar Abdur Rab Nishtar (for the Muslim League). To the left are Jawaharlal Nehru, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel and Acharya Kripalani (for the Congress) and Baldev Singh (representing the Sikhs). Seated behind Lord Mountbatten are General Lord Ismay (right), his chief of staff, and Sir Eric Miéville (left), his private secretary.

It is June 3, 1947, and failed viceregal initiatives, such as the Simla Conference, the London Conference and the Cabinet Mission Plan – even the killings of Direct Action Day – are matters to be left behind. All hopes for a united India are dead. The sole question is how to proceed with the division of India.

Lord Mountbatten announces the British Government’s plan for the Partition of India, to be implemented under the Indian Independence Act, 1947. British India will be divided into two new and fully sovereign dominions with effect from August 15, 1947. Bengal and Punjab will be partitioned between the two new dominions. Legislative authority is conferred upon the Constituent Assemblies of the two dominions and British suzerainty over the Princely States ends on August 15, 1947.

The meeting is followed by separate broadcasts on All India Radio by Lord Mountbatten, Mr Nehru, Mr Jinnah and Mr Singh.

This is the parting of ways. A few weeks later, Mr Jinnah and Mr Nehru assume their responsibilities respectively in Karachi and Delhi.

A lawyer by training, Nawabzada Liaquat Ali Khan enters politics in 1923. Throughout the struggle for Pakistan, he is a close associate and friend of Mr Jinnah. After Mr Jinnah’s death, his name appears as one of three executors of his will.

He serves as Pakistan’s first prime minister until his assassination on the grounds of Company Bagh, Rawalpindi, in 1951.

A PLAN TO NOWHERE

CALCUTTA AUGUST 16, 1946

THE AFTERMATH

As dusk descends, the results of the riots that erupt on Direct Action Day are all too clear. It is a day of untrammelled rioting and slaughter between Hindus and Muslims.

Trouble starts in the morning, even before the Muslim League rally, scheduled for noon at the Ochterlony Monument, begins. The Premier of Bengal, Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy and his predecessor, Khawaja Nazimuddin are the main speakers. Tensions rise and Khawaja Nazimuddin pleads for restraint.

The moment the rally is over, the crowd, incensed by unconfirmed reports that all the injured are Muslims, start attacking Hindu-owned shops. Hindus and Sikhs lie in wait; as soon as they catch a Muslim, they hack him into pieces. By six o’clock a curfew is imposed; at eight o’clock troops secure the main routes and conduct patrols.

Although the worst affected areas are brought under control by late afternoon and the army presence is extended overnight, the killing escalates the next day. In the slums and areas outside military control, the violence gains in intensity. On August 18, buses and taxis loaded with Sikhs and Hindus armed with swords, iron bars and firearms appear. The communal slaughter continues unabated until August 21, when Bengal is placed under Viceroy Rule.

The violence claims an estimated 3,000 dead and 17,000 injured.

CALCUTTA AUGUST 1946

FACING THE UNKNOWABLE

Mr Suhrawardy is the last premier of Bengal under the Raj. He is a prominent leader of the Muslim League and serves as mayor of Calcutta in the 1930s. In ten years’ time, he will be Pakistan’s fifth prime minister. Two years later, Khawaja Nazimuddin will be Pakistan’s second governor general and subsequently Pakistan’s second prime minister.

One month earlier, the Muslim League and Congress, for different reasons, reject the Cabinet Mission Plan. The Congress are intransigent in their opposition to any kind of equal Muslim representation at the centre. It is clear that agreement cannot be reached and Mr Jinnah announces a countrywide Direct Action Day on August 16, 1946 to demonstrate the Muslim League’s determination that any arrangement following a British withdrawal must include parity at the centre.

As Direct Action Day breaks, no one can predict that the events that unfold will come to be known as the Great Calcutta Killings. Meetings and processions take place all across India, and all with minimal disturbance – with one exception – Calcutta. Perhaps because the situation in Bengal is particularly complex.

Although Muslims represent the majority of the population (56%), they are concentrated in eastern Bengal. In Calcutta, the ratio is reversed and Hindus constitute 64% of the population. As a result, Calcutta’s population is divided into two antagonistic entities.

Adding fuel to fire, tensions are running high. Hindu and Muslim communal newspapers are whipping up public sentiment with inflammatory reporting. And on the day itself, political leaders fail to anticipate the emotional response the word ‘nation’ evokes; it is no longer a political slogan – it has become a reality, politically and in the popular imagination.

Against this backdrop, Direct Action Day becomes symbolic of the carnage Hindu-Muslim antagonism will trigger in the days leading up, and subsequent, to Partition.

It is a day neither the Muslim League, the Congress nor the British administration could foresee.

DELHI JULY 1946

RENOUNCING THE PLAN

Earlier the same year, the Cabinet Mission, appointed by the British Government, is in India to find a solution that will grant independence to India, while attempting to preserve some semblance of the country’s unity.

They draw up a plan that calls for the setting up of a Constituent Assembly composed of members of the Congress and the Muslim League. The plan includes two options.

Option one is an all-India Federation based on the grouping of a) the Hindu majority provinces b) the Muslim majority provinces in the northwest (to include Sindh, Balochistan, Punjab and the NWFP) and the Muslim majority provinces in the northeast (to include Bengal and Assam). The powers of the federal centre under option one are to be limited to defence, foreign affairs and communications. Although acceptable to the Muslim League, this option is rejected by the Congress, which is firmly opposed to the grouping of provinces and the restrictions placed on central powers.

Option two proposes a sovereign Pakistan based on the partition of Punjab and Bengal, with all the Muslim majority areas going to Pakistan. Option two is rejected by both the Muslim League and the Congress, the latter reiterating that they will never forego their national character, accept parity with the Muslim League or agree to a veto by any communal group.

Once it becomes clear that the Congress wants to break the grouping and enhance central powers, Mr Jinnah withdraws the Muslim League’s approval of option one, reiterates the demand for a sovereign Pakistan based on undivided Punjab and Bengal, and calls for a Direct Action Day to force the British to grant them equal representation at the centre.

The die is now cast.

THE VICEREGAL CHESS GAME

SIMLA & LONDON 1945-46

IN THE VICEREGAL SHADOW

Mr Jinnah is on his way to attend the Simla Conference called at the behest of the Viceroy, Lord Wavell on June 25, 1945. The purpose is to discuss the Wavell Plan with the Muslim League and the Congress.

The Wavell Plan is the outcome of discussions in May 1945 between Lord Wavell and the British Government about the future of India. The crux of the plan is the reconstitution of the Viceroy’s Executive Council, with members selected by the Viceroy from a list of nominees proposed by the political parties. Differences immediately arise between the Muslim League and the Congress on the issue of Muslim representation. The Muslim League’s position is that as the only representative party of Muslims in India, all Muslim representatives on the Council must be nominated by them.

The Congress maintain that as they represent all communities in India they, therefore, should nominate Muslim representatives. The result is a deadlock and failure.

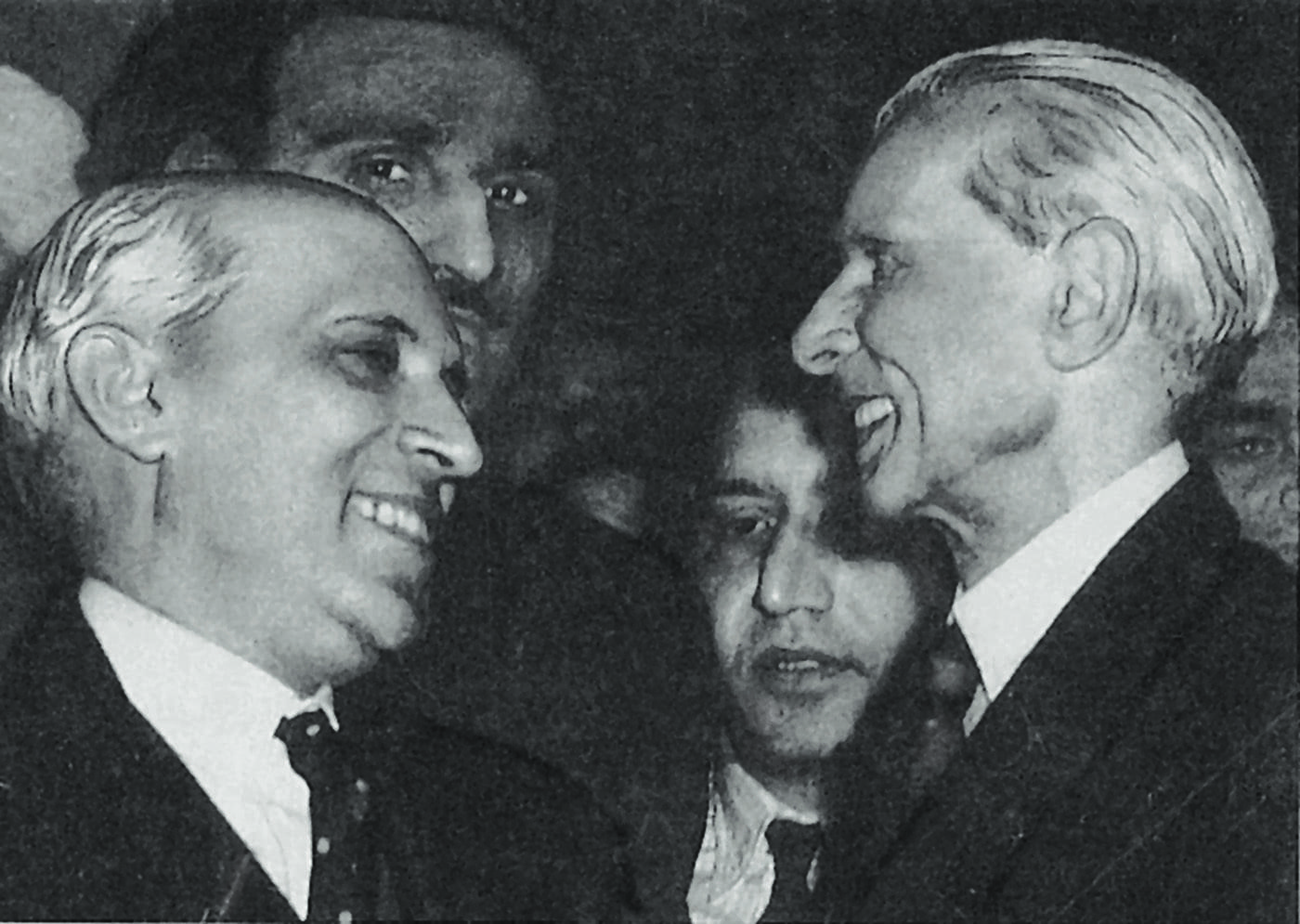

Mr Jinnah and Mr Nehru are attending the London Conference, chaired by British Prime Minister Clement Attlee. This is a further attempt by the British to secure acceptance of the Cabinet Mission Plan. Although Mr Jinnah is willing to consider maintaining links with Hindustan (as the future Hindu majority state is referred to) on subjects such as a joint military and communications, he is adamant in his refusal to any agreement with respect to the composition of the Constituent Assembly without the constitutional stipulations required for the protection of future Muslim rights.

Subsequent to the failure of the London Conference, Mr Jinnah insists on a fully sovereign Pakistan with dominion status. The encounter of smiles at the India Office did not work.

DELHI 1946

A REDSHIRT POET DISSENTS

Ghani Khan is the eldest son of Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan. Educated at Rabindranath Tagore’s Shantiniketan School in western Bengal, which Indira Gandhi also attends, he is a poet, a sculptor, a painter – and a man of strong political views.

In April 1947, as Partition approaches, he forms a militant group, Pakhtoon Zalmay (Pakhtoon Youth), aimed at protecting the Redshirts and members of Congress from ‘violence’ at the hands of Muslim League sympathisers. However, the relationship between Congress and the Redshirt Movement is on a downward spiral. Despite Redshirt opposition to Pakistan, Congress negotiations with the British over the Partition of India stipulate for a referendum to be held on whether the NWFP will join Pakistan or India. Bitterly disappointed by this turn of events, his father’s last words to Mahatma Gandhi and his Congress allies are: “You have thrown us to the wolves.”

The referendum is overwhelmingly in favour of Pakistan; the Redshirts severe their connection with Congress and move a resolution, whereby the Redshirts “regard Pakistan as their own country and pledge to do their utmost to strengthen and safeguard its interests and make every sacrifice for the cause.”

From then on, although no longer active in politics, Ghani Khan is still seen as a symbol of dissent and spends much of the early 1950s in prison. After his release, he withdraws into philosophy and art and authors several volumes of poems, including De Panjray Chaghar, a literary defence of the Pakhtoonwali code of honour. In 1980, General Zia-ul-Haq confers the Sitara-e-Imtiaz upon him.

He dies in 1996; his legacy is best expressed in his words: “Pakhtoon is not merely a race but a state of mind; there is a Pakhtoon inside every man, who at times wakes up, and it overpowers him.”

PESHAWAR TO BOMBAY 1944

GANDHI MANOEUVERS

Mahatma Gandhi visits the NWFP in the mid-1930s in order to consolidate the alliance between the Indian National Congress and Abdul Ghaffar Khan’s Redshirt Movement. It is the proximity between Abdul Ghaffar Khan and Mahatma Gandhi that earns the former the sobriquet of the ‘Frontier Gandhi’.

The Redshirt Movement begins as a non-violent struggle against British rule by Pakhtoons under the leadership of Abdul Ghaffar Khan. The movement starts facing pressure from the British authorities and Abdul Ghaffar Khan seeks political allies with the national parties.

Rebuffed by the Muslim League in 1931, he finds a sympathetic ear with the Congress. His brother, Dr Khan Sahib, plays an instrumental role in the success of the Congress-Redshirt Alliance in the 1937 and 1946 elections. As Partition approaches, the Redshirt Movement opposes joining Pakistan and when the Congress agrees to the British proposal for a referendum in the NWFP, Abdul Ghaffar Khan’s relationship with the Congress finds itself seriously frayed.

Initiated by Mahatma Gandhi in July 1944, the talks are held at Mr Jinnah’s residence in Bombay in September. Mahatma Gandhi’s objective is to convince Mr Jinnah that the idea of Pakistan is untenable. In his opinion, power should be transferred to the Congress, after which Muslim majority areas that vote for separation will be made part of an Indian federation.

This view, says Mahatma Gandhi, reflects the substance of the Lahore Resolution. For Mr Jinnah, the absence of any guarantee that would protect Muslim rights under such an arrangement makes the proposal completely unacceptable. The talks end in failure.

ENTER THE QUAID-I-AZAM

KARACHI 1943

A PROCESSION IN TRIUMPH

Behind them and standing are Mr Jinnah’s National Guard ADCs; Mumtaz Hidayatullah, the son of Ghulam Hussain Hidayatullah, the veteran politician from Sindh, and Saeed Haroon, the son of Haji Abdullah Haroon.

On March 3, 1943, G.M. Syed brings before the Sindh Legislative Assembly, a resolution demanding the creation of Pakistan. The resolution is adopted, making it the first one in favour of the creation of Pakistan passed by a legislature in undivided India. It states that the Muslims of India “are justly entitled to the right as a single separate nation to have independent national states of their own, carved in the zones in which they are in majority in the subcontinent of India…”

It is this triumph for the Muslim League that frames Mr Jinnah’s arrival later in December to attend the Annual Session of the Muslim League for which Karachi is chosen as the venue.

As the President of the Sindh Muslim League, G.M. Syed is tasked with the responsibility of organising the arrangements for the Annual Session. He writes: “For nearly three months we worked to make a grand job of the honour that had been done to us. We did not spare men or material in lending all the grandeur and splendour to this historic session and only those who attended it can bear testimony to the scrupulous care with which every detail had been attended to and the lavish hospitality that Sindh had to offer.”

In his memoir, Struggle For New Sindh, G.M. Syed also writes about his admiration for Mr Jinnah: “In Jinnah I found a man of extraordinary intellectual capacity. His domineering personality and dynamic genius left a deep impression on my mind.”

G.M. Syed is subsequently asked by Mr Jinnah to resign from the presidency of the Sindh Muslim League, after which a group largely drawn from the Sindh Muslim League and styled as the Progressive Muslim League contest the 1945-46 elections in Sindh and establish a path of their own.

LAHORE MARCH 23, 1940

THE MOMENT OF TRUTH

The Quaid-i-Azam, Mohammad Ali Jinnah addresses a mammoth crowd in Lahore’s Minto Park on March 22, 1940, subsequent to the passing of the Lahore Resolution at the three-day Annual Session of the Muslim League.

In the photograph above, Nawab Shahnawaz Khan Mamdot, the Chairman of the Punjab Reception Committee for the session, stands behind him, adjacent to the flagpole.

Sir Zafarullah Khan (first from left) is credited with the original drafting of the Resolution; the critical points were then submitted in a memorandum to the Viceroy, Lord Linlithgow, in Delhi. The draft was subsequently further amended in Lahore by the Working Committee. The main supporters of the Resolution, one each from the north-western Muslim majority states in India, are (from second left) Maulana Zafar Ali Khan (Punjab), Maulana Abdul Ghafoor Hazarvi (NWFP), Haji Abdullah Haroon (Sindh) and Qazi Isa (Balochistan).

The Quaid-i-Azam, Mohammad Ali Jinnah and Nawabzada Liaquat Ali Khan peruse the Lahore Resolution as Chaudhry Khaliquzzaman, the seconder of the Resolution and the leader of the Muslim League in the UP legislature, delivers a fiery oration.

Unanimously accepted, the Resolution declares: “No constitutional plan would be workable or acceptable to the Muslims unless geographical contiguous units are demarcated into regions, which should be so constituted with such territorial readjustments as may be necessary.”

In the long journey to Pakistan, a critical point has been reached. Nothing will be the same again. It is the moment of truth.

SINDH 1938

A REMARKABLE HOMECOMING

Haji Abdullah Haroon, President of the Sindh Muslim League relaxes at home in Seafield House between sessions of the Karachi Conference. The Quaid-i-Azam, Mohammad Ali Jinnah and Mian Mumtaz Daultana are in an animated discussion about the revitalisation of the first All India Muslim League government in Sindh headed by Haji Abdullah Haroon.

Mr Jinnah, once looked upon as the ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity, returns to India in 1934 to assume the presidency of the Muslim League after four years in self-imposed exile in London. His return is marked by three vigorous years during which he consolidates the foundations of what will eventually constitute the future territories of Pakistan (although Pakistan is still not yet an inevitability in his mind).

Specifically, he succeeds in pushing back the Unionist style coalitions in Sindh, which by their composition are dependent upon the intervention of the British Governor. This pushback culminates in the resolution moved by Shaikh Abdul Majeed and adopted at the Karachi Conference recommending that the Muslim League develop a plan for Muslims to attain full independence.

This is an important first step in Mr Jinnah’s journey towards Muslim independence and a remarkable homecoming.

Four years later, in 1942, Haji Abdullah Haroon passes away. Mr Jinnah in his tribute says: “Muslim India, especially Sindh, has lost a leader who served and guided the people loyally and faithfully. I have lost a friend and colleague and deeply mourn his death.”

Nawabzada Liaquat Ali Khan describes him as “a pillar of strength to the Muslim League and one of its most sincere leaders. He was a staunch Pakistanist. His death is an irreparable loss to Muslim India in general and to Sindh in particular.”

THE DAYS IN THE WILDERNESS

ALLAHABAD 1930

AN ADDRESS TO REMEMBER

Sir Muhammad Iqbal arrives at the landmark session of the Muslim League in Allahabad on December 30, 1930, to deliver the now famous Allahabad Address.

Seated in the Lanchester on the right is Haji Abdullah Haroon. Standing next to the car is a young Yusuf Haroon; standing at the extreme left is poet Hafeez Jullundhri who will pen Pakistan’s national anthem eighteen years later.

In his address, Sir Muhammad Iqbal sets out his vision of an independent state for the Muslim majority provinces of undivided India. He defines the Muslims of India as a nation and suggests there is no possibility of peace in India until they are recognised as a nation under a federal system whereby Muslim majority units are accorded the same privileges given to Hindu majority units.

In outlining a vision of an independent state for Muslim majority provinces for north-western India, Iqbal is the first politician to articulate the two-nation theory; that Muslims are a distinct nation deserving political independence from the other regions and communities of India.

Sir Muhammad Iqbal’s eight stanza masterpiece, Masjid-e-Qurtuba, is inspired by his prayers at the mosque and includes the following lines: “The stars gaze upon your precincts as a piece of heaven/But alas! For centuries your porticoes have not resonated with the call of the azaan”; an allusion to the turning point when Cordoba returned to Christian rule in 1236 and the mosque became a Roman Catholic cathedral.

LONDON 1931

A SELF-IMPOSED EXILE

The Round Table Conferences in London have ended in failure. Mr Jinnah decides to stay on in London where he has a thriving practice as a Privy Council lawyer, with chambers located on King’s Bench Walk.

He spends long periods brooding over the collapse of the Hindu-Muslim unity platform in the Indian National Congress.

Finally, in 1934, he is persuaded to return to India to assume the presidency of the All India Muslim League. Thereafter, as the Quaid-i-Azam, he launches a series of initiatives that within a record time span of thirteen years, lead to the establishment of Pakistan.

Ruttie Jinnah is the daughter of Parsi baronet, Sir Dinshaw Petit. She marries the Quaid at the age of eighteen in 1918, despite virulent family opposition. The couple reside in South Court Mansion in Bombay.

Ruttie and Mr Jinnah are a glamorous couple. Flawless in her silks, Ruttie wears her signature hairstyle adorned with fresh flowers or complemented with headbands, embellished with diamonds, rubies and emeralds.

The couple are happy in the early years of their marriage. However, by 1923, Mr Jinnah’s deepening political involvement, long hours and frequent travel leave Ruttie feeling lonely and increasingly fragile.

He is in Delhi when a call comes through on February 20, 1929 with the news that Ruttie is critically ill.

According to a close friend, Mr Jinnah says:

“Do you know who that was? It was my father-in-law. This is the first time we have spoken since my marriage.”

What Mr Jinnah does not know is that Ruttie is already dead.

The funeral is held at Bombay’s Muslim cemetery on February 22, 1929. According to Ruttie’s friend, Kanji Dwarkadas, “the funeral was a painfully slow ritual. Jinnah sat silent through all five hours.”

Then as Ruttie’s body is lowered into the grave, Mr Jinnah is the first to throw a handful of earth on the body. Suddenly, he breaks down and weeps like a child.

Another friend, M.C. Chagla, said years later that “there were tears in his eyes. That was the only time I found Jinnah betraying some shadow of human weakness.”

A FIRE EXTINGUISHED 1919-1931

THE KHILAFAT MOVEMENT

Maulana Muhammad Ali Jauhar (left) dons Turkish attire on his visit to Turkey on the eve of the First World War. Dr Mukhtar Ahmed Ansari, leader of the Indian Muslim Medical Mission to Turkey and future president of the Muslim League, stands on the right.

The firebrand Ali Brothers from Rampur State, achieve legendary status within the Khilafat Movement (1919 -1922), as the crucible in which a separate South Asian Muslim identity takes shape.

Maulana Muhammad Ali Jauhar makes his mark at the end of the First World War, when the Ottoman Empire is occupied by the Allied Powers under the Treaty of Sèvres. The Turkish Nationalists reject the Treaty, and the Grand National Assembly under Mustafa Kemal Atatürk denounces the rule of the reigning sultan, Mehmed VI.

As these events unfold, Maulana Muhammad Ali Jauhar and his brother, Maulana Shaukat Ali, launch an agitation in India aimed at building up political unity among Muslims and pressure the British to preserve the Ottoman caliphate.

The agitation leads to the formation of the Khilafat Movement. However, despite an alliance with the Indian National Congress and a nationwide campaign of peaceful civil disobedience, the Khilafat Movement itself weakens, because Indian Muslims are divided between working for the Congress, the Khilafat Movement and the Muslim League.

The end comes in 1924 when Atatürk abolishes the caliphate. The brothers join the Muslim League and play a major role in the Pakistan Movement.

The Khilafat Movement is a major step towards the establishment of a separate Muslim state in South Asia.

Maulana Shaukat Ali (extreme right) in January 1931 sits next to the coffin of his brother, Maulana Muhammad Ali Jauhar, on board the ship SS Narkunda on the way to Port Said. Maulana Muhammad Ali Jauhar is buried within the precincts of the Masjid Al-Aqsa in Jerusalem.

His frequent jail sentences and acute diabetes have an adverse impact on his health. He dies in London in January 1931, while attending the First Round Table Conference.

His final words to the British Government are: “I would prefer to die in a foreign country as long as it is free. If you do not grant us freedom in India, you will have to find me a grave here.”

GENESIS DHAKA 1906

THE ALL INDIA MUSLIM LEAGUE

Nawab Viqar-ul-Mulk (first from left), a prominent political personality from Hyderabad State, inaugurates the founding session of the All India Muslim League in Dhaka in 1906.

Nawab Salimullah of Dhaka (second from left), a venerated educationist, legislator and a powerful advocate for the Partition of Bengal, hosts the session of the All India Muhammadan Educational Conference in Dhaka; a session that leads to the foundation of the All India Muslim League.

Sir Sultan Mohammed Shah Aga Khan III (third from left), the spiritual head of the Ismaili community worldwide, plays a formative role in the founding of the All India Muslim League and serves as President from 1907 to 1913. He later becomes president of the League of Nations.

The founding members of the All India Muslim League (above and below) at the baradariof Shah Bagh in Dhaka on December 30, 1906.

The image below shows Maulana Muhammad Ali Jauhar seated on the front row, second from left, and his brother Maulana Shaukat Ali, sixth from left, same row.

The All India Muslim League which grows from the vision of Sir Syed Ahmed Khan at Aligarh will spearhead the creation of Pakistan in 1947.

TOWARDS 1947

CARAVAN TO FREEDOM

As Partition approaches in 1947, large convoys of Sikh and Hindu refugees head towards East Punjab, and Muslims flee to the two wings of Pakistan. This photo captures the tail end of this momentous period.

This content has been independently produced by Dawn Media Group. UBL has paid for association with the content.

UBL, one of the largest banks in the private sector, was declared Pakistan’s Best Bank in 2016. With a proud legacy of 58 years, UBL is part of the socio-economic fabric of the country and has always served Pakistan with passion and pride. To mark Pakistan’s 70th independence year, this campaign celebrates everything that makes us proud of our past and positive for our future.