By AKBAR S. AHMED

Routledge

Understanding Jinnah

Islam gave the Muslims of India a sense of identity; dynasties like the Mughals gave them territory; poets like Allama Iqbal gave them a sense of destiny. Jinnah’s towering stature derives from the fact that, by leading the Pakistan movement and creating the state of Pakistan, he gave them all three. For the Pakistanis he is simply the Quaid-i-Azam or the Great Leader. Whatever their political affiliation, they believe there is no one quite like him.

Jinnah: a lifeMohammed Ali Jinnah was born to an ordinary if comfortable household in Karachi, not far from where Islam first came to the Indian subcontinent in AD 711 in the person of the young Arab general Muhammad bin Qasim. However, Jinnah’s date of birth — 25 December 1876 — and place of birth are presently under academic dispute.

Just before Jinnah’s birth his father, Jinnahbhai Poonja, had moved from Gujarat to Karachi. Significantly, Jinnah’s father was born in 1857 — at the end of one kind of Muslim history, with the failed uprisings in Delhi — and died in 1901 (F. Jinnah 1987: vii).

Jinnah’s family traced its descent from Iran and reflected Shia, Sunni and Ismaili influences; some of the family names — Valji, Manbai and Nathoo — were even ‘akin to Hindu names’ (F. Jinnah 1987: 50). Such things mattered in a Muslim society conscious of underlining its non-Indian origins, a society where people gained status through family names such as Sayyed and Qureshi (suggesting Arab descent), Ispahani (Iran) and Durrani (Afghanistan). Another source has a different explanation of Jinnah’s origins. Mr Jinnah, according to a Pakistani author, said that his male ancestor was a Rajput from Sahiwal in the Punjab who had married into the Ismaili Khojas and settled in Kathiawar (Beg 1986: 888). Although born into a Khoja (from khwaja or ‘noble’) family who were disciples of the Ismaili Aga Khan, Jinnah moved towards the Sunni sect early in life. There is evidence later, given by his relatives and associates in court, to establish that he was firmly a Sunni Muslim by the end of his life (Merchant 1990).

One of eight children, young Jinnah was educated in the Sind Madrasatul Islam and the Christian Missionary Society High School in Karachi. Shortly before he was sent to London in 1893 to join Graham’s Shipping and Trading Company, which did business with Jinnah’s father in Karachi, he was married to Emibai, a distant relative (F. Jinnah 1987: 61). It could be described as a traditional Asian marriage — the groom barely 16 years old and the bride a mere child. Emibai died shortly after Jinnah left for London; Jinnah barely knew her. But another death, that of his beloved mother, devastated him (ibid.).

Jinnah asserted his independence by making two important personal decisions. Within months of his arrival he left the business firm to join Lincoln’s Inn and study law. In 1894 he changed his name by deed poll, dropping the ‘bhai’ from his surname. Not yet 20 years old, in 1896 he became the youngest Indian to pass. As a barrister, in his bearing, dress and delivery Jinnah cultivated a sense of theatre which would stand him in good stead in the future.

It has been said that Jinnah chose Lincoln’s Inn because he saw the Prophet’s name at the entrance. I went to Lincoln’s Inn looking for the name on the gate, but there is no such gate nor any names. There is, however, a gigantic mural covering one entire wall in the main dining hall of Lincoln’s Inn. Painted on it are some of the most influential lawgivers of history, like Moses and, indeed, the holy Prophet of Islam, who is shown in a green turban and green robes. A key at the bottom of the painting matches the names to the persons in the picture. Jinnah, I suspect, was not deliberately concealing the memory of his youth but recalling an association with the Inn of Court half a century after it had taken place. He had remembered there was a link, a genuine appreciation of Islam. Had those who have written about Jinnah’s recollection bothered to visit Lincoln’s Inn the mystery would have been solved. However, knowledge of the pictorial depiction of the holy Prophet would certainly spark protests; demands from the active British Muslim community for the removal of the painting would be heard in the UK.

In London Jinnah had discovered a passion for nationalist politics and had assisted Dadabhai Naoroji, the first Indian Member of Parliament. During the campaign he became acutely aware of racial prejudice, but he returned to India to practise law at the Bombay Bar in 1896 after a brief stopover in Karachi. He was then the only Muslim barrister in Bombay (see plate 1).

Jinnah was a typical Indian nationalist at the turn of the century, aiming to get rid of the British from the subcontinent as fast as possible. He adopted two strategies: one was to try to operate within the British system; the other was to work for a united front of Hindus, Muslims, Christians and Parsees against the British. He succeeded to an extent in both.

Jinnah’s conduct reflected the prickly Indian expression of independence. On one occasion in Bombay, when Jinnah was arguing a case in court, the British presiding judge interrupted him several times, exclaiming, ‘Rubbish.’ Jinnah responded: ‘Your honour, nothing but rubbish has passed your mouth all morning.’ Sir Charles Ollivant, judicial member of the Bombay provincial government, was so impressed by Jinnah that in 1901 he offered him permanent employment at 1,500 rupees a month. Jinna declined, saying he would soon earn that amount in a day. Not too long afterwards he proved himself correct.

Stories like these added to Jinnah’s reputation as an arrogant nationalist. His attitude towards the British may be explained culturally as well as temperamentally. He was not part of the cultural tradition of the United Provinces (UP) which had revolved around the imperial Mughal court based in Delhi and which smoothly transferred to the British after they moved up from Calcutta. Exaggerated courtesy, hyperbole, dissimulation, long and low bows, salaams that touched the forehead repeatedly — these marked the deference of courtiers to imperial authority. Even Sir Sayyed Ahmad Khan, one of the most illustrious champions of the Muslim renaissance in the late nineteenth century, came from a family that had served the Mughals, but had readily transferred his loyalties to the British.

Jinnah often antagonized his British superiors. Yet he was clever enough consciously to remain within the boundaries, pushing as far as he could but not allowing his opponents to penalize him on a point of law. In short he learned to use British law skilfully against the British.

At several points in his long career, Jinnah was threatened by the British with imprisonment on sedition charges for speaking in favour of Indian home rule or rights. He was frozen out by those British officials who wished their natives to be more deferential. For example, Lord Willingdon, Viceroy of India in 1931-6, did not take to him, and even the gruff but kindly Lord Wavell, Viceroy in 1943-7, was made to feel uncomfortable by Jinnah’s clear-minded advocacy of the Muslims, even though he recognized the justice of Jinnah’s arguments. The last Viceroy, however, Lord Mountbatten, could not cope with what he regarded as Jinnah’s arrogance and haughtiness, preferring the natives to be more friendly and pliant.

Ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unityOn his return from England in 1896, Jinnah joined the Indian National Congress. In 1906 he attended the Calcutta session as secretary to Dadabhai Naoroji, who was now president of Congress. One of his patrons and supporters, G. K. Gokhale, a distinguished Brahmin, called him ‘the best ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity’. He was correct. When Bal Gangadhar Tilak, the Hindu nationalist, was being tried by the British on sedition charges in 1908 he asked Jinnah to represent him.

On 25 January 1910 Jinnah took his seat as the ‘Muslim member from Bombay’ on the sixty-man Legislative Council of India in Delhi. Any illusions the Viceroy, Lord Minto, may have harboured about the young Westernized lawyer as a potential ally were soon laid to rest. When Minto reprimanded Jinnah for using the words ‘harsh and cruel’ in describing the treatment of the Indians in South Africa, Jinnah replied: ‘My Lord! I should feel much inclined to use much stronger language. But I am fully aware of the constitution of this Council, and I do not wish to trespass for one single moment. But I do say that the treatment meted out to Indians is the harshest and the feeling in this country is unanimous’ (Wolpert 1984: 33).

Jinnah was an active and successful member of the (mainly Hindu) Indian Congress from the start and had resisted joining the Muslim League until 1913, seven years after its foundation. None the less, Jinnah stood up for Muslim rights. In 1913, for example, he piloted the Muslim Wakfs (Trust) Bill through the Viceroy’s Legislative Council, and it won widespread praise. Muslims saw in him a heavyweight on their side. For his part, Jinnah thought the Muslim League was ‘rapidly growing into a powerful factor for the birth of a United India’ and maintained that the charge of ‘separation’ sometimes levelled at Muslims was extremely wide of the mark. On the death of his mentor, Gokhale, in 1915, Jinnah was struck with ‘sorrow and grief’ (Bolitho 1954: 62), and in May 1915 he proposed that a memorial to Gokhale be constructed. A few weeks later in a letter to The Times of India he argued that the Congress and League should meet to discuss the future of India, appealing to Muslim leaders to keep pace with their Hindu ‘friends’.

Jinnah was elected president of the Lucknow Muslim League session in 1916 (from now he would be one of its main leaders, becoming president of the League itself from 1920 to 1930 and again from 1937 to 1947 until after the creation of Pakistan). Jinnah’s political philosophy was revealed in the Lucknow conference in the same year when he helped bring the Congress and the League on to one platform to agree on a common scheme of reforms. Muslims were promised 30 per cent representation in provincial councils. A common front was constructed against British imperialism. The Lucknow Pact between the two parties resulted. Presiding over the extraordinary session, he described himself as ‘a staunch Congressman’ who had ‘no love for sectarian cries’ (Afzal 1966: 56-62).

This was the high point of his career as ambassador of the two communities and the closest the Congress and the Muslim League came. About this time, he fell in love with a Parsee girl, Rattanbai (Ruttie) Petit, known as ‘the flower of Bombay’. Sir Dinshaw Petit, her father and a successful businessman, was furious, since Jinnah was not only of a different faith but more than twice her age, and he refused his consent to the marriage. As Ruttie was under-age, she and Jinnah waited until she was 18, in 1918, and then got married. Shortly before the ceremony Ruttie converted to Islam. In 1919 their daughter Dina was born.

By this time even the British recognized Jinnah’s abilities. Edwin Montagu, the Secretary of State for India, wrote of him in 1917: ‘Jinnah is a very clever man, and it is, of course, an outrage that such a man should have no chance of running the affairs of his own country’ (Sayeed 1968: 86).

Jinnah cut a handsome figure at this time, as described in a standard biography by an American professor: ‘Raven-haired with a moustache almost as full as Kitchener’s and lean as a rapier, he sounded like Ronald Coleman, dressed like Anthony Eden, and was adored by most women at first sight, and admired or envied by most men’ (Wolpert 1984: 40). A British general’s wife met him at a viceregal dinner in Simla and wrote to her mother in England:

After dinner, I had Mr. Jinnah to talk to. He is a great personality. He talks the most beautiful English. He models his manners and clothes on Du Maurier, the actor, and his English on Burke’s speeches. He is a future Viceroy, if the present system of gradually Indianizing all the services continues. I have always wanted to meet him, and now I have had my wish. (Raza 1982: 34)

Mrs Sarojini Naidu, the nationalist poet, was infatuated: to her, Jinnah was the man of the future (see her ‘Mohammad Ali Jinnah — ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity’, in J. Ahmed 1966). He symbolized everything attractive about modern India. Although her love remained unrequited she wrote him passionate poems; she also wrote about him in purple prose worthy of a Mills and Boon romance:

Tall and stately, but thin to the point of emaciation, languid and luxurious of habit, Mohammad Ali Jinnah’s attenuated form is a deceptive sheath of a spirit of exceptional vitality and endurance. Somewhat formal and fastidious, and a little aloof and imperious of manner, the calm hauteur of his accustomed reserve but masks, for those who know him, a naive and eager humanity, an intuition quick and tender as a woman’s, a humour gay and winning as a child’s. Pre-eminently rational and practical, discreet and dispassionate in his estimate and acceptance of life, the obvious sanity and serenity of his worldly wisdom effectually disguise a shy and splendid idealism which is of the very essence of the man. (Bolitho 1954: 21-2)

However, Gandhi’s emergence in the 1920s — and the radically different style of politics he introduced which drew in the masses — marginalized Jinnah. The increasing emphasis on Hinduism and the concomitant growth in communal violence worried Jinnah. Throughout the decade he remained president of the Muslim League but the party was virtually non-existent. The Congress had little time for him now, and his unrelenting opposition to British imperialism did not win him favour with the authorities. As we shall see in later chapters, he was a hero in search of a cause.

In 1929, while Jinnah was vainly attempting to make sense of the uncertain political landscape, Ruttie died. Jinnah felt the loss grievously. He moved to London with his daughter Dina and his sister Fatima, and returned to his career as a successful lawyer. At this point, Jinnah’s story appeared to have concluded as far as the Indian side was concerned.

Securing a financial baseJinnah had successfully resolved the dilemma of all those who wished to challenge British colonialism. He had secured himself financially. Sir Sayyed Ahmad Khan had to compromise; Jinnah did not. This difference was made possible by developments in the early part of the century: Indians could now enter professions which gave them financial and social security irrespective of their political opinions. Earlier, Indians had been seen as either friendly or hostile natives. The former were encouraged, the latter were victimized, often losing their lands and official positions.

Jinnah’s lifestyle resembled that of the upper-class English professional. Jinnah prided himself on his appearance. He was said never to wear the same silk tie twice and had about 200 hand-tailored suits in his wardrobe. His clothes made him one of the best-dressed men in the world, rivalled in India perhaps only by Motilal Nehru, the father of Jawaharlal. Jinnah’s daughter called him a ‘dandy’, ‘a very attractive man’. Expensive clothes, perhaps an essential accessory of a successful lawyer in British India, were Jinnah’s main indulgence. In spite of his extravagant taste in dress Jinnah remained careful with money throughout his life (he rebuked his ADC for over-tipping the servants at the Governor’s house in Lahore in 1947 — G. H. Khan 1993: 81). Dina recounts her father commenting on the two communities: ‘If Muslims got ten rupees they would buy a pretty scarf and eat a biriani whereas Hindus would save the money.’

In the early 1930s Jinnah lived in a large house in Hampstead, London, had an English chauffeur who drove his Bentley and an English staff to serve him. There were two cooks, Indian and Irish, and Jinnah’s favourite food was curry and rice, recalls Dina. He enjoyed playing billiards. Dina remembers her father taking her to the theatre, pantomimes and circuses.

In the last years of his life, as the Quaid-i-Azam, Jinnah increasingly adopted Muslim dress, rhetoric and thinking. Most significant from the Muslim point of view is the fact that the obvious affluence was self-created. Jinnah had not exploited peasants as the feudal lords had done, nor had he made money like corrupt politicians through underhand deals, nor had he been bribed by any government into selling his conscience. What he owned was made legally, out of his skills as a lawyer and a private investor. By the early 1930s he was reportedly earning 40,000 rupees a month at the Bar alone (Wolpert 1984:138) — at that time an enormous income. Jinnah was considered, even by his opponents like Gandhi, one of the top lawyers of the subcontinent and therefore one of the most highly paid. He also had a sharp eye for a good investment, successfully dabbling in property. His houses were palatial: in Hampstead in London, on Malabar Hill in Bombay and at 10 Aurangzeb Road in New Delhi, a house designed by Edwin Lutyens. His wealth gave him an independence which in turn enabled him to speak his mind.

Paradoxically, Jinnah’s behaviour reflected as much Anglo-Indian sociology as Islamic theology. His thriftiness to the point of being parsimonious, his punctuality, his integrity, his bluntness, his refusal to countenance sifarish (nepotism) were alien to South Asian society (see chapter 4). Yet these were the values he had absorbed in Britain. He later attempted to weld his understanding of Islam to them. His first two speeches in the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan in 1947 reflect some of the ideas of a Western liberal society and his attempts to find more than an echo of them in Islamic history from the time of the holy Prophet (see chapter 7). Jinnah was attempting a synthesis.

Creating a countryIn the early 1930s several important visitors came to Jinnah’s Hampstead home, requesting him to return to India to lead the Muslim League. Eventually he was persuaded and finally returned in 1935. With little time for preparation, he led the League into the 1937 elections. Its poor showing did not discourage him; instead, he threw himself into reorganizing it. The Muslim League session in 1937 in Lucknow was a turning point and generated wide enthusiasm (see chapter 3). A snowball effect became apparent. In 1939, now in his early sixties, Jinnah made his last will, appointing his sister Fatima, his political lieutenant Liaquat Ali Khan and his solicitor as joint executors and trustees of his estate. Although Fatima was the main beneficiary, he did not forget his daughter Dina and his other siblings. He also remembered his favourite educational institutions, especially Aligarh, which helped lay the foundations for Pakistan.

Jinnah’s fine clothes and erect bearing helped to conceal the fact that he was in poor physical health. From 1938 onwards he was to be found complaining of ‘the tremendous strain’ on his ‘nerves and physical endurance’ (Jinnah’s letter to Hassan Ispahani written on 12 April of that year in the Ispahani Collection). From then on he regularly fell ill, yet that was carefully hidden from the public. He remained unwell for much of the first half of 1945. Later in the year he admitted: ‘The strain is so great that I can hardly bear it’ (to Ispahani, 9 October 1945, Ispahani Collection). His doctors, Dr Jal Patel and Dr Dinshah Mehta, ordered him to take it easy, to rest, but the struggle for Pakistan had begun and Jinnah was running out of time.

Although by now called the Quaid-i-Azam, the Great Leader, Jinnah never courted titles. He had refused a knighthood and even a doctorate from his favourite university:

In 1942, when the Muslim University, Aligarh, had wished to award him an honorary Degree of Doctor of Laws, he refused saying: ‘I have lived as plain Mr. Jinnah and I hope to die as plain Mr. Jinnah. I am very much averse to any title or honours and I will be more happy if there was no prefix to my name.’ (Zaidi 1993: volume I, part I, xlv)

Not all Muslims looked up to Jinnah. Many criticized him, some because they found him too Westernized, others because he was too straight and uncompromising. One young man, motivated by religious fervour and belonging to the Khaksars, a religious party, attempted to assassinate him on 26 July 1943. Armed with a knife he broke into Jinnah’s home in Bombay and succeeded in wounding him before he was overpowered. Jinnah publicly appealed to his followers and friends to ‘remain calm and cool’ (Wolpert 1984: 225). The League declared 13 August a day of thanksgiving throughout India.

In 1940 Jinnah presided over the League meeting in which the Lahore Resolution was moved calling for a separate Muslim homeland. In 1945-6 the Muslim League triumphed in the general elections. The League was widely recognized as the third force in India along with the Congress and the British. Even Jinnah’s opponents now acknowledged him: Gandhi addressed him as Quaid-i-Azam. The Muslim masses throughout India were now with him, seeing in him an Islamic champion.

By the time Mountbatten came to India as Viceroy in 1947 Jinnah was dying; he would be dead in 1948. Neither the British nor the Congress suspected the gravity of Jinnah’s illness. Many years later Mountbatten confessed that had he known he would have delayed matters until Jinnah was dead; there would have been no Pakistan.

There were several dramatic twists and turns on the way to Pakistan, with Jinnah trying to negotiate the best possible terms to satisfy the high expectations and emotions of the Muslims. Pakistan was finally conceded in the summer of 1947, with Jinnah as its Governor-General. It was, in his words, ‘moth-eaten’ and ‘truncated’, but still the largest Muslim nation in the world. In Karachi, its capital, as Governor-General Jinnah delivered two seminal speeches to the Constituent Assembly on 11 and 14 August (see chapter 7). Suddenly, at the height of his popularity, Jinnah resigned the presidency of the League.

Despite his legendary reserve and the seriousness of his position, Jinnah retained his quiet sense of humour. As Governor-General, when he was almost worshipped in Pakistan, he was told that a certain young lady had said she was in love with his hands (Bolitho 1954: 213). Shortly afterwards, she was seated near him at a function, and Jinnah mischievously asked her not to keep looking at his hands. The lady was both thrilled and embarrassed at having amused the Quaid-i-Azam.

By now his health was seriously impaired. He was suffering from tuberculosis, and his heavy smoking — fifty cigarettes a day of his favourite brand, Craven A — and punishing work schedule had also taken their toll. Jinnah died on 11 September 1948 at the age of 71. The nation went into deep mourning (see plates 4 and 15). Quite spontaneously, hundreds of thousands of people joined the burial procession — a million people, it was estimated. They felt like orphans; their father had died. Dina, on her only visit to Pakistan, recalls ‘the tremendous hysteria and grief’.

The grief was genuine. Those present at the burial itself or those who heard the news still look back on that occasion as a defining moment in their lives. They felt an indefinable sense of loss, as if the light had gone out of their lives. (As a typical example take the case of Sartaj Aziz, a distinguished Pakistani statesman. He remembers the impact that hearing of Jinnah’s death had on him. He had fainting fits for three days. His mother said that he did not respond in the same manner to his own father’s death.) A magnificent mausoleum in Karachi was built to honour Jinnah.

This, then, is the bare bones of Jinnah’s life.

The role of Jinnah’s familyThe closest members of Jinnah’s family were his sister Fatima, his wife Ruttie and their daughter, their only child, Dina. Ruttie and Dina are problematic for many Pakistanis, especially for sociological and cultural reasons. For the founder of the nation — the Islamic Republic of Pakistan — to have married a Parsee appears inexplicable to most Pakistanis. Jinnah’s orthodox critics taunted him, composing verses about him marrying a kafirah, a female infidel (Khairi 1995: 468; see also G. H. Khan 1993: 77): ‘He gave up Islam for the sake of a Kafirah / Is he the Quaid-i-Azam [great leader] or the Kafir-i-Azam [great kafir]?’

Dina is seen by many as the daughter who deserted her father by marrying a Christian. Because she did not go to live in Pakistan Dina is regarded as ‘disloyal’. Pakistanis have blotted out Ruttie and Dina from their cultural and historical consciousness. Thus Professor Sharif al Mujahid, a conscientious and sympathetic biographer and former director of the Quaid-i-Azam Academy in Karachi, does not mention either woman in his 806-page volume (1981). Nor did the archives, pictorial exhibitions and official publications contain more than the odd picture of the two. Someone appears to have been busy eliminating their photographs.

It is almost taboo to discuss Jinnah’s personal life in Pakistan; Ruttie and Dina, his beloved wife and daughter, have both been blacked out from history. None the less, it is through a study of his family that we see Jinnah the man and understand him more than at any other point in his life because that is when he exposes his inner feelings to us.

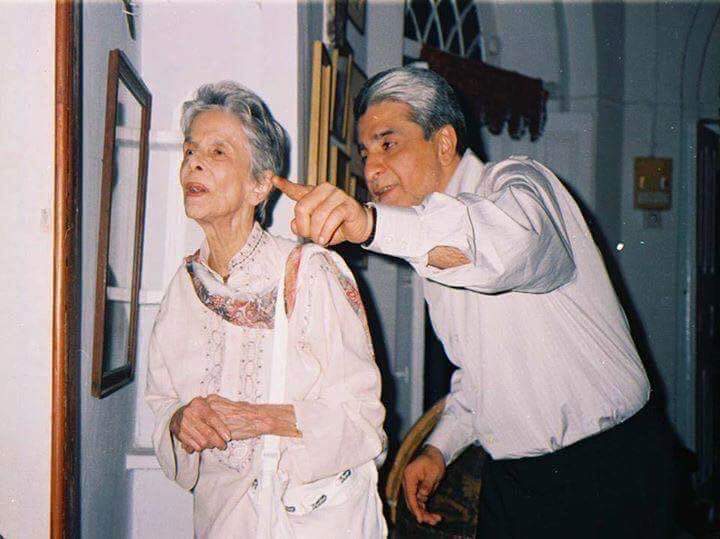

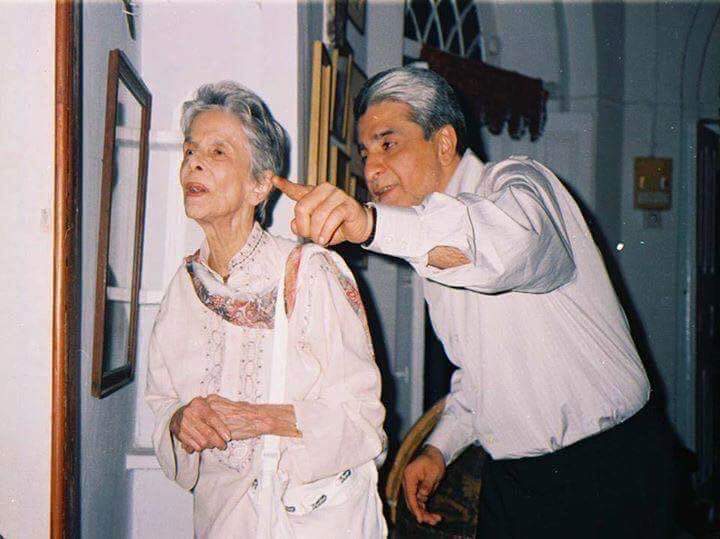

Fatima: sister of JinnahThe relationship between Jinnah and his sister Fatima (see plate 2) is important in helping us to understand Jinnah, the Muslim movement leading to Pakistan and Pakistan history. Her name of course comes from that of the Prophet’s daughter and symbolizes traditional Muslim family life. Born in 1893, Fatima was a constant source of strength to her brother, and after his death she remained the symbol of a democratic Pakistan true to his spirit, a symbol of modern Muslim womanhood. Closest to Jinnah of his siblings in looks and spirit, Fatima is known as the Madr-e-Millat, Mother of the Nation, in Pakistan.

After their father’s death in 1901, Jinnah became her guardian, first securing her education as a boarder at a convent when she was nine in 1902 and then enrolling her in a dental college in Calcutta in 1919. In 1923 he helped her set up a clinic in Bombay. All this was done in the face of opposition at home because Muslim society of the time discouraged Western education and Western professions for its women (F. Jinnah 1987: xvii). When Ruttie died, Fatima gave up her career as a dentist at the age of 36 and moved into Jinnah’s house to run it and look after Dina; she then accompanied Jinnah on his voluntary exile in London. She accepted the role of her brother’s confidante, friend, assistant and chief ally.

Fatima attended the League session in 1937 and all the annual sessions from 1940 onwards when she took on the role of organizing women in favour of the League. She was with her brother on his triumphant plane journey to Pakistan from Delhi and stepped out with him on the soil of the independent nation that he had created in August 1947.

In the last years she was anxious that Jinnah was burning himself out in the pursuit of Pakistan. When she expressed concern for his health he would reply that one man’s health was insignificant when the very existence of a hundred million Muslims was threatened. ‘Do you know how much is at slake?’ he would ask her (F. Jinnah 1987: 2). She was the last person to see him on his deathbed.

Yahya Bakhtiar, a senator from Baluchistan who was sensitive to the issue of notions of women’s honour in Baluch society, pointed out that in those days not even British male politicians encouraged their womenfolk to take a public role as Jinnah did. After Pakistan had been created he asked Fatima Jinnah to sit beside him on the stage at the Sibi Darbar, the grand annual gathering of Baluch and Pukhtun chiefs and leaders at Sibi. He was making a point: Muslim women must take their place in history. The Sibi Darbar broke all precedents.

Fatima’s behaviour echoed that of her brother. Zeenat Rashid, daughter of Sir Abdullah Haroon, a leader of Sind who was one of Jinnah’s followers, said that although the Jinnahs stayed in her family home in Karachi for weeks at a time there was never a hint of moral or financial impropriety. They would never accept presents; indeed no one would dare to give any. There was no lavish spending at government expense. On the contrary, the joke was that when Fatima Jinnah was in charge of the Governor-General’s house after the creation of Pakistan the suppliers would be in dismay. ‘She has ordered half a dozen bananas … or half a dozen oranges because six people will have lurch,’ they would moan. The ADCs would ring Zeenat Rashid and say they wished to come to her house for a good meal; they were hungry. Jinnah’s broad Muslim platform was also echoed by his sister years after his death, as quoted by Liaquat Merchant: ‘I said, “Miss Jinnah even you are born a Shia.” To this she remarked, “I am not a Shia, I am not a Sunni, I am a Mussalman.” She also added that the Prophet of Islam has given us Muslim Religion and not Sectarian Religion’ (Merchant 1990: 165).

Later in life, retired and reclusive, she once again entered public life. In the mid-1960s, as a frail old woman she took on Field Marshal Ayub Khan, then at the height of his power, in an attempt to restore democracy. To challenge a military dictator is a commendable act of courage in Pakistan. She came very close to toppling him, in spite of the vote-rigging and corruption:

A combined opposition party with Fatima Jinnah, sister of the Quaid-i-Azam (Founder of the Nation), Mohammed Ali Jinnah, as its candidate won a majority in three of the country’s sixteen administrative divisions — Chittagong, Dacca, and Karachi. Despite a concerted political campaign on the part of the government, Fatima Jinnah received 36 percent of the national vote and 47 percent of the vote in East Pakistan. (Sisson and Rose 1990: 19)

Fatima was bitter about the way Pakistan had treated her and dishonoured the memory of her brother by the use of martial law, and by corruption and mismanagement. The strain of the campaign hastened her end and she died in 1967, just after the elections, at the age of 74. She is buried within the precincts of Jinnah’s mausoleum in Karachi. Fatima Jinnah remains an unsung heroine of the Pakistan movement. A fierce nationalist, a determined woman of integrity and principle, she reflected the characteristics of her brother.

(C) 1997 Akbar S. Ahmed All rights reserved. ISBN: 0-415-14965-7

http://www.nytimes.com/books/first/a/ahmed-jinnah.html

![Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah and Miss Fatima Jinnah enjoying a boat ride, possibly in Dhaka, in the early 1940s. Standing on the left [wearing sherwani] is Khawaja Nazimuddin, who was at the time the Premier of Bengal. | Photo: The Press Information Department, Ministry of Information, Broadcasting & National Heritage, Islamabad (PID)](https://i.dawn.com/primary/2017/09/59b3d7602302f.jpg)

Iqbal received his early education in the traditional maktab. Later he joined the Sialkot Mission School, from where he passed his matriculation examination. In 1897, he obtained his Bachelor of Arts Degree from Government College, Lahore. Two years later, he secured his Masters Degree and was appointed in the Oriental College, Lahore, as a lecturer of history, philosophy and English. He later proceeded to Europe for higher studies. Having obtained a degree at Cambridge, he secured his doctorate at Munich and finally qualified as a barrister.

Iqbal received his early education in the traditional maktab. Later he joined the Sialkot Mission School, from where he passed his matriculation examination. In 1897, he obtained his Bachelor of Arts Degree from Government College, Lahore. Two years later, he secured his Masters Degree and was appointed in the Oriental College, Lahore, as a lecturer of history, philosophy and English. He later proceeded to Europe for higher studies. Having obtained a degree at Cambridge, he secured his doctorate at Munich and finally qualified as a barrister.