Context of ‘1987: Pakistan Secretly Builds Nuclear Weapon’

This is a scalable context timeline. It contains events related to the event 1987: Pakistan Secretly Builds Nuclear Weapon. You can narrow or broaden the context of this timeline by adjusting the zoom level. The lower the scale, the more relevant the items on average will be, while the higher the scale, the less relevant the items, on average, will be.

May 18, 1974: India Tests First Nuclear Device

India detonates a nuclear device in an underground facility. The device had been built using material supplied for its ostensibly peaceful nuclear program by the United States, France, and Canada. The test, and this aspect of India’s nuclear program, is unauthorized by global control mechanisms. India portrays the test as a “peaceful nuclear explosion,” and says it is “firmly committed” to using nuclear technology for only peaceful purposes.

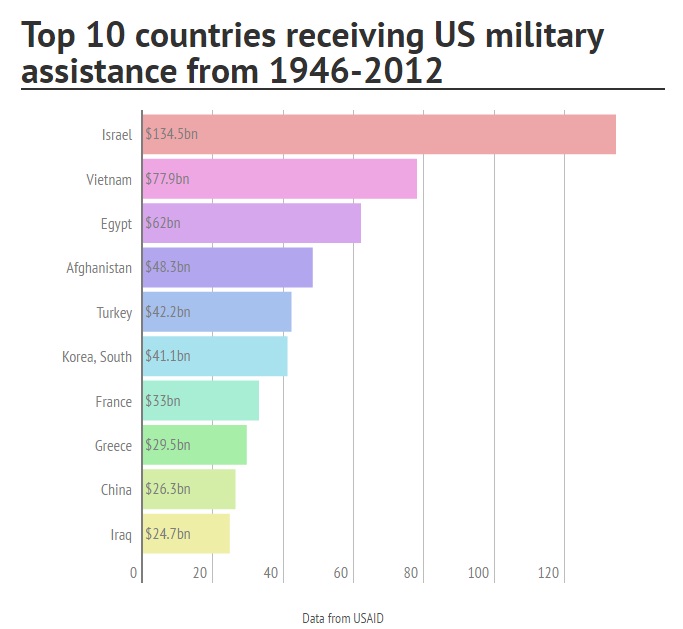

Kissinger: ‘Fait Accompli’ – Pakistan, India’s regional opponent, is extremely unhappy with the test, which apparently confirms India’s military superiority. Due to the obvious difficulties producing its own nuclear bomb, Pakistan first tries to find a diplomatic solution. It asks the US to provide it with a nuclear umbrella, without much hope of success. Relations between Pakistan and the US, once extremely close, have been worsening for some years. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger tells Pakistan’s ambassador to Washington that the test is “a fait accompli and that Pakistan would have to learn to live with it,” although he is aware this is a “little rough” on the Pakistanis.

No Punishment – No sanctions are imposed on India, or the countries that sold the technology to it, and they continue to help India’s nuclear program. Pakistani foreign minister Agha Shahi will later say that, if Kissinger had replied otherwise, Pakistan would have not started its own nuclear weapons program and that “you would never have heard of A. Q. Khan.” Shahi also points out to his colleagues that if Pakistan does build a bomb, then it will probably not suffer any sanctions either.

Pakistan Steps up Nuclear Program – Pakistani Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto then decides that his country must respond to this “grave and serious threat” by making its own nuclear weapons. He steps up Pakistan’s nuclear research efforts in a quest to build a bomb, a quest that will be successful by the mid-1980s (see 1987). [LEVY AND SCOTT-CLARK, 2007, PP. 11-14; ARMSTRONG AND TRENTO, 2007, PP. 39-40]

1981: Pakistan Begins Digging Tunnels for Nuclear Program; Work Noticed by India, Israel

At some time in 1981, Pakistan begins digging some tunnels under the Ras Koh mountains. The work is apparently related to Pakistan’s nuclear weapons program, which begins preparation for a cold test of a nuclear weapon this year (see Shortly After May 1, 1981). This work is noticed by both India and Israel, who also see other signs that work is continuing on Pakistan’s nuclear weapons program. Tunnels in these mountains will be used when Pakistan tests nuclear weapons in 1998 (see May 28, 1998). [LEVY AND SCOTT-CLARK, 2007, PP. 86, 275]

1985: Secretary of State Schulz Says Pakistan Will Not Get Bomb, but Knows They Already Have Nuclear Program

George Schulz, secretary of state in the Reagan administration, says, “We have full faith in [Pakistan’s] assurance that they will not make the bomb.” However, the US, including the State Department, is already aware that Pakistan has a nuclear weapons program (see 1983 and August 1985-October 1990). [GUARDIAN, 10/13/2007]

August 1985-October 1990: White House Defies Congress and Allows Pakistan’s Nuclear Weapons Program to Progress

In 1985, US Congress passes legislation requiring US economic sanctions on Pakistan unless the White House can certify that Pakistan has not embarked on a nuclear weapons program (see August 1985 and August 1985). The White House certifies this every year until 1990 (see 1987-1989). However, it is known all the time that Pakistan does have a continuing nuclear program. For instance, in 1983 a State Department memo said Pakistan clearly has a nuclear weapons program that relies on stolen European technology. Pakistan successfully builds a nuclear bomb in 1987 but does not test it to keep it a secret (see 1987). With the Soviet-Afghan war ending in 1989, the US no longer relies on Pakistan to contain the Soviet Union. So in 1990 the Pakistani nuclear program is finally recognized and sweeping sanctions are applied (see June 1989). [GANNON, 2005]Journalist Seymour Hersh will comment, “The certification process became farcical in the last years of the Reagan Administration, whose yearly certification—despite explicit American intelligence about Pakistan’s nuclear-weapons program—was seen as little more than a payoff to the Pakistani leadership for its support in Afghanistan.” [NEW YORKER, 3/29/1993] The government of Pakistan will keep their nuclear program a secret until they successfully test a nuclear weapon in 1998 (see May 28, 1998).

1987: Pakistan Secretly Builds Nuclear Weapon

Pakistan successfully builds a nuclear weapon around this year. The bomb is built largely thanks to the illegal network run by A. Q. Khan. Pakistan will not actually publicly announce this or test the bomb until 1998 (see May 28, 1998), partly because of a 1985 US law imposing sanctions on Pakistan if it were to develop nuclear weapons (see August 1985-October 1990). [HERSH, 2004, PP. 291]However, Khan will tell a reporter the program has been successful around this time (see March 1987).

March 1987: A. Q. Khan Says Pakistan Has Nuclear Weapons, then Retracts Claims

A. Q. Khan. [Source: CBC]A. Q. Khan, father of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons program, tells an Indian reporter that the program has been successful (see 1987). “What the CIA has been saying about our possessing the bomb is correct,” he says, adding, “They told us Pakistan could never produce the bomb and they doubted my capabilities, but they now know we have it.” He says that Pakistan does not want to use the bomb, but “if driven to the wall there will be no option left.” The comments are made during a major Indian army exercise known as Brass Tacks that Pakistanis consider a serious threat, as it is close to the Pakistani border. In fact, at one point the Indian commanding general is reported to consider actually attacking Pakistan—an attack that would be a sure success given India’s conventional superiority. According to reporter Seymour Hersh, the purpose of the interview is “to convey a not very subtle message to the Indians: any attempt to dismember Pakistan would be countered with the bomb.” This interview is an embarrassment to the US government, which aided Pakistan during the Soviet-Afghan War, but has repeatedly claimed Pakistan does not have nuclear weapons (see August 1985-October 1990). Khan retracts his remarks a few days later, saying he was tricked by the reporter. [NEW YORKER, 3/29/1993]

June 1989: Bush Administration Decides to Cut Off Aid to Pakistan over Nuclear Weapons Program Next Year

President George Bush and Secretary of State James Baker decide that the US will cut off foreign aid to Pakistan because of its nuclear weapons program. Pakistan was a major recipient of foreign aid during the Soviet Afghan war, when the US channeled support to the mujaheddin through it, but Soviet forces began withdrawing from Afghanistan in February (see February 15, 1989). It is decided that aid will be provided for 1989, but not for 1990 (see October 1990). [NEW YORKER, 3/29/1993]

August 4, 1989: Analyst of Pakistan’s Nuclear Program Alleged to Be ‘Security Risk’ and Fired from Pentagon

Richard Barlow, an analyst who has repeatedly insisted that Pakistan has a nuclear weapons program (see July 1987 or Shortly After and Mid-1989), is fired from his position at the Pentagon. Barlow will later say, “They told me they had received credible information that I was a security risk.” When he asks why he is thought to be a security risk, “They said they could not tell me as the information was classified,” but “senior Defense Department officials” are said to have “plenty of evidence.” His superiors think he might leak information about Pakistan’s nuclear program to congressmen in favor of the non-proliferation of nuclear weapons. He spends the next eighteen months in the Pentagon personnel pool, under surveillance by security officers. Apparently, I. Lewis “Scooter” Libby and two officials who work for Undersecretary of Defense for Policy Paul Wolfowitz are involved in the sacking. It is also rumored that Barlow is a Soviet spy. Barlow’s conclusions about Pakistan’s nuclear program are unpopular with some, because if the US admitted the nuclear program existed, this would lead to a break between the US and Pakistan and endanger US aid to the anti-Soviet mujaheddin and US arms sales (see August 1985-October 1990 and August-September 1989). After he is fired, rumors are started saying that Barlow is a tax evader, alcoholic, adulterer, and in psychiatric care. As his marriage guidance counseling is alleged to be cover for the psychiatric care, the Pentagon insists that investigators be allowed to interview his marriage guidance counselor. Due to this and other problems, his wife leaves him and files for divorce. [NEW YORKER, 3/29/1993; GUARDIAN, 10/13/2007] Barlow will later be exonerated by various investigations (see May 1990 and Before September 1993).

Fall 1990: US Tells Pakistan to Destroy Nuclear Weapon Cores, but It Does Not Do So

In a letter handed to Pakistani Foreign Minister Sahibzada Yaqub Khan, the US demands that Pakistan destroy the cores of its nuclear weapons, thus disabling the weapons. Pakistan does not do so. The US then imposes sanctions on Pakistan (see October 1990), such as cutting off US aid to it, due to the nuclear weapons program. However, it softens the blow by waiving some of the restrictions (see 1991-1992). [NEW YORKER, 3/29/1993] The US has known about Pakistan’s nuclear weapons program for some time, but continued to support the Pakistanis during the Soviet-Afghan War (see August 1985-October 1990).

October 1990: US Imposes Sanctions on Pakistan

Since 1985, US Congress has required that sanctions be imposed on Pakistan if there is evidence that Pakistan is developing a nuclear weapons program (see August 1985-October 1990). With the Soviet-Afghan war over, President Bush finally acknowledges widespread evidence of Pakistan’s nuclear program and cuts off all US military and economic aid to Pakistan. However, it appears some military aid will still get through. For instance, in 1992, Senator John Glenn will write, “Shockingly, testimony by Secretary of State James Baker this year revealed that the administration has continued to allow Pakistan to purchase munitions through commercial transactions, despite the explicit, unambiguous intent of Congress that ‘no military equipment or technology shall be sold or transferred to Pakistan.’” [INTERNATIONAL HERALD TRIBUNE, 6/26/1992] These sanctions will be officially lifted a short time after 9/11.

September 10, 1996: UN Adopts Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty; US First to Sign

The United Nations adopts the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) banning the testing of nuclear weapons. The UN General Assembly votes 158-3 to adopt the CTBT, with India (see June 20, 1996), Bhutan, and Libya voting against it, and Cuba, Lebanon, Syria, Mauritius, and Tanzania abstaining. US President Bill Clinton will be the first to sign the treaty, followed by 70 other nations, including Britain, China, France, and Russia. By November 1997, 148 nations will sign the treaty. [NUCLEAR THREAT INITIATIVE, 4/2003; FEDERATION OF AMERICAN SCIENTISTS, 12/18/2007] In 1999, the Times of India will observe that from the US’s viewpoint, the CTBT will primarily restrict India and Pakistan from continuing to develop their nuclear arsenals (see May 11-13, 1998 and May 28, 1998), and will delay or prevent China from developing more technologically advanced “miniaturized” nuclear weapons such as the US already has. It will also “prevent the vertical proliferation and technological refinement of existing arsenals by the other four nuclear weapons states.” [TIMES OF INDIA, 10/16/1999] Two years later, the US Senate will refuse to ratify the treaty (see October 13, 1999).

May 11-13, 1998: India Tests Five Nuclear Devices

India, which has refused to sign the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) banning nuclear testing (see September 10, 1996), shocks the world by testing five nuclear devices over the course of three days. The largest is a 42-kiloton thermonuclear device. [FEDERATION OF AMERICAN SCIENTISTS, 12/18/2007] India’s rival Pakistan will conduct its own nuclear tests two weeks later (see May 28, 1998). Indian political scientist and nuclear critic Kanti Bajpai will later say: “Whatever Indians say officially, there is a status attached to the bomb. The five permanent members of the UN Security Council are all nuclear powers.” [NEW YORK TIMES, 5/4/2003]

May 28, 1998: Pakistan Tests Nuclear Bomb

Pakistan’s first nuclear test take place underground but shakes the mountains above it. [Source: Associated Press]Pakistan conducts a successful nuclear test. Former Clinton administration official Karl Inderfurth later notes that concerns about an Indian-Pakistani conflict, or even nuclear confrontation, compete with efforts to press Pakistan on terrorism. [US CONGRESS, 7/24/2003] Pakistan actually built its first nuclear weapon in 1987 but kept it a secret and did not test it until this time for political reasons (see 1987). In announcing the tests, Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif declares, “Today, we have settled the score.” [NEW YORK TIMES, 5/4/2003]

Pakistan’s first nuclear test take place underground but shakes the mountains above it. [Source: Associated Press]Pakistan conducts a successful nuclear test. Former Clinton administration official Karl Inderfurth later notes that concerns about an Indian-Pakistani conflict, or even nuclear confrontation, compete with efforts to press Pakistan on terrorism. [US CONGRESS, 7/24/2003] Pakistan actually built its first nuclear weapon in 1987 but kept it a secret and did not test it until this time for political reasons (see 1987). In announcing the tests, Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif declares, “Today, we have settled the score.” [NEW YORK TIMES, 5/4/2003]

May 30, 1998: Pakistan Conducts Last of Six Nuclear Bomb Tests, Plutonium Possibly Used

Pakistan conducts the sixth and last of a series of nuclear bomb tests that started two days earlier (see May 28, 1998). Samples taken by US aircraft over the site indicate that the test may have involved plutonium, whereas uranium bombs were used for the other five. After the US learns that the tests are witnessed by Kang Thae Yun, a North Korean involved in that country’s proliferation network (see Early June 1998), and other North Korean officials, it will speculate that the final test was performed by Pakistan for North Korea, which is better known for its plutonium bomb program. Authors Adrian Levy and Catherine Scott-Clark will comment, “In terms of nuclear readiness, this placed North Korea far ahead of where the CIA had thought it was, since [North Korea] had yet to conduct any hot tests of its own.” [LEVY AND SCOTT-CLARK, 2007, PP. 278]

July 1998: US Unfreezes Agricultural Aid to Pakistan

The US again begins to provide agricultural aid to Pakistan, although its provision had been frozen in the wake of Pakistani nuclear weapons tests in May (see May 28, 1998 and May 30, 1998). The US will again begin to provide military and technological assistance three months later (see October 1998). [LEVY AND SCOTT-CLARK, 2007, PP. 286]

July 15, 1998: Rumsfeld’s Ballistic Missile Committee Says Chief Threat to US Is from Iran, Iraq, and North Korea

Congressional conservatives receive a second “alternative assessment” of the nuclear threat facing the US that is far more to their liking than previous assessments (see December 23, 1996). A second “Team B” panel (see November 1976), the Commission to Assess the Ballistic Missile Threat to the United States, led by former Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld and made up of neoconservatives such as Paul Wolfowitz and Stephen Cambone, finds that, contrary to earlier findings, the US faces a growing threat from rogue nations such as Iran, Iraq, and North Korea, who can, the panel finds, inflict “major destruction on the US within about five years of a decision.” This threat is “broader, more mature, and evolving more rapidly” than previously believed. The Rumsfeld report also implies that either Iran or North Korea, or perhaps both, have already made the decision to strike the US with nuclear weapons. Although Pakistan has recently tested nuclear weapons (see May 28, 1998), it is not on the list. Unfortunately for the integrity and believability of the report, its methodology is flawed in the same manner as the previous “Team B” reports (see November 1976); according to author J. Peter Scoblic, the report “assume[s] the worst about potential US enemies without actual evidence to support those assumptions.” Defense analyst John Pike is also displeased with the methodology of the report. Pike will later write: “Rather than basing policy on intelligence estimates of what will probably happen politically and economically and what the bad guys really want, it’s basing policy on that which is not physically impossible. This is really an extraordinary epistemological conceit, which is applied to no other realm of national policy, and if manifest in a single human being would be diagnosed as paranoia.” [GUARDIAN, 10/13/2007; SCOBLIC, 2008, PP. 172-173] Iran, Iraq, and North Korea will be dubbed the “Axis of Evil” by George W. Bush in his 2002 State of the Union speech (see January 29, 2002).

October 1998: US Unfreezes Military and Technological Assistance to Pakistan

The US again begins to provide Pakistan with military and technological aid, which had been frozen in the wake of Pakistani tests of nuclear weapons in May (see May 28, 1998 and May 30, 1998). The US also froze agricultural aid after the tests, but began to provide it again in July (see July 1998). [LEVY AND SCOTT-CLARK, 2007, PP. 286]

Nawaz Sharif meeting with US Defense Secretary William Cohen at the Pentagon on December 3, 1998. [Source: US Department of Defense]Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif comes to Washington to meet with President Clinton and other top Clinton administration officials. The number one issue for Clinton is Pakistan’s nuclear program, since Pakistan had recently illegally developed and exploded a nuclear weapon (see May 28, 1998). The second most important issue is Pakistan’s economy; the US wants Pakistan to support free trade agreements. The third most important issue is terrorism and Pakistan’s support for bin Laden. Author Steve Coll will later note, “When Clinton himself met with Pakistani leaders, his agenda list always had several items, and bin Laden never was at the top. Afghanistan’s war fell even further down.” Sharif proposes to Clinton that the CIA train a secret Pakistani commando team to capture bin Laden. The US and Pakistan go ahead with this plan, even though most US officials involved in the decision believe it has almost no chance for success. They figure there is also little risk or cost involved, and it can help build ties between American and Pakistani intelligence. The plan will later come to nothing (see October 1999). [COLL, 2004, PP. 441-444]

March 14, 2003: President Bush Waives Last Remaining US Sanctions on Pakistan

President Bush waives the last set of US sanctions against Pakistan. The US imposed a new series of sanctions against Pakistan in 1998, after Pakistan exploded a nuclear weapon (see May 28, 1998), and in 1999, when President Pervez Musharraf overthrew a democratically elected government (see October 12, 1999). The lifted sanctions had prohibited the export of US military equipment and military assistance to a country whose head of government has been deposed. Some other sanctions were waived shortly after 9/11. Bush’s move comes as Musharraf is trying to decide whether or not to support a US-sponsored United Nations resolution which could start war with Iraq. It also comes two weeks after 9/11 mastermind Khalid Shaikh Mohammed was captured in Pakistan (see February 29 or March 1, 2003). [AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE, 3/14/2003]