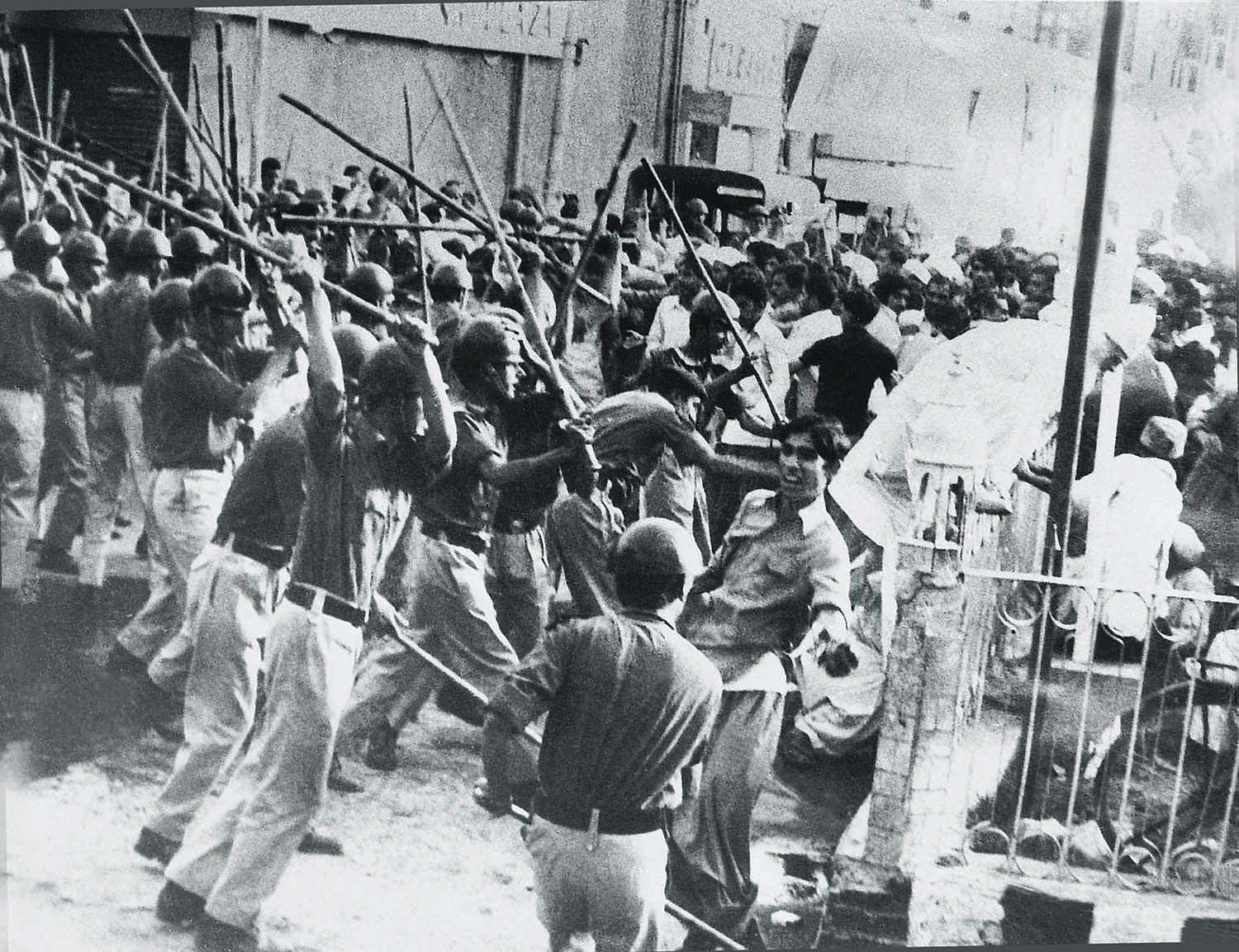

The crowds waved when Zulfikar Ali Bhutto addressed them. The crowds waved when he was removed.

From ecstasy to angst, Bhutto’s equation with the masses experienced a complete spectrum of emotions that, arguably, remains unparalleled in national political history. | Photo: Arif Ali

Authoritarianism and the downfall

By S. Akbar Zaidi

SOME historians have made the suggestion that there are two phases to Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s five-and-a-half years in power. In the first phase, one sees a pro-poor, populist Bhutto, supported by many urban leftists in his party, who undertakes a number of far-reaching structural economic and social reforms – from land reforms to nationalisation and social-sector interventions. He is also given credit for having seen Pakistan’s first democratically agreed to Constitution approved and passed by a parliament based on universal franchise. His stature as a crafty negotiator helped him deal with Pakistani nationalists, as it did with Indira Gandhi in Simla in 1972.

This first phase lasted perhaps three years, somewhere into 1974, but soon after, one begins to see a different Bhutto; one who discards his radical allies and moves towards his landed and feudal base, making him authoritarian and dictatorial, abandoning the social groups that had been responsible for his phenomenal rise.

Bhutto was many things to many people and constituencies, playing different roles as circumstances demanded. He could be a democrat but also mercilessly authoritarian; a benevolent feudal with modernist tendencies; a nationalist with regional aspirations; and a secularist courting Islamists. Perhaps it was for these multiple and often contradictory reasons that no political leader in Pakistan has been as reviled or cherished as is Bhutto even four decades after his death.

A YEAR OF UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCES

At least four events in 1974 had a major bearing on what was to happen to Bhutto and to Pakistan, with long-term consequences that have had an impact even to this day.

In February 1974, Bhutto was able to organise and host the Second Islamic Summit Conference in Lahore, with as many as 35 heads of state and government present.

From Shah Faisal of Saudi Arabia to the popular Muammar Qadhafi of Libya to the revolutionary Yasser Arafat, Bhutto was able to make a political statement about Pakistan’s position in the Muslim world. He also used this opportunity to recognise Bangladesh by inviting Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.

With the first OPEC oil price rise in 1973, which led to the westernisation and modernisation of the oil-rich states, Bhutto opened the doors to the Gulf states and to the Middle East for Pakistan’s migrant labour and its remittance economy; still a key pillar of Pakistan’s economy with numerous unintended consequences. Ironically, it was Gen Ziaul Haq who benefitted the most from these ties, and, in many ways, one can make the argument that the close ties with Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states changed the social, religious and political composition of Pakistan in ways which would have made Bhutto most uncomfortable.

Ayesha Jalal makes the assertion, though unfortunately provides no evidence for this, that during the Islamic Summit, “King Faisal indicated to Bhutto that Saudi aid [to Pakistan] would be contingent on Pakistan declaring Ahmadis a non-Muslim minority”. Other scholars have given far more domestically-oriented reasons and arguments for why the community was declared a minority by the National Assembly unanimously in September 1974. The consequences of this move, in which Bhutto participated, continue unabated to this day, again in ways that Bhutto would not have recognised. Today, it indicates why and how the idea of a just and inclusive notion of Pakistani citizenship failed.

The third major development in 1974 was India’s nuclear test in May. While Bhutto had the ambitions to build nuclear weapons some years prior to India going nuclear, Pakistan’s ‘Islamic Bomb’ was to be acquired even if we had “to eat grass”.

One further development in November 1974 was to cost Bhutto his life. The murder of Nawab Mohammad Ahmad Khan Kasuri, the father of dissident PPP leader Ahmed Raza Kasuri, who, many believe, was the intended target, was blamed on Bhutto, and the case was opened against him once he had been deposed by Zia in 1977, leading to Bhutto’s execution on April 4, 1979.

All these events in 1974 were to have far-reaching implications, years and decades from when they took place, beyond Bhutto’s life. In July 1974, one of the old guards of the original PPP, J.A. Rahim, the first secretary-general of the party, was beaten up brutally by Bhutto’s personal henchmen, the Federal Security Force, supposedly on Bhutto’s orders. This was just one indication of the growing authoritarianism of Pakistan’s first elected leader.

Other incidents occurred during the course of Bhutto’s reign, where editors and publishers of newspapers critical of his policies were often roughed up and threatened. Both the editors of Dawn and Jasarat were arrested under Bhutto’s increasingly draconian regime. Also not spared were nationalist leaders like Khan Abdul Wali Khan, as the National Awami Party (NAP) was banned in February 1975 after the murder of Hayat Khan Sherpao, a senior PPP leader who some saw as a contender to Bhutto, in Peshawar. Wali Khan and others were incarcerated in the Hyderabad Conspiracy case, and were later released only when the walls around Bhutto started to close in.

CREATING AN OPPOSITION

While Bhutto certainly gave the awam, the working people, political consciousness for the very first time through his reforms and rhetoric, he also alienated this very constituency by moving away from many of his earlier promises. Moreover, given his reforms, he was bound to accumulate many enemies along the way. From landlords to business groups, from religious parties to groups that saw Bhutto’s ways as ‘un-Pakistani’ and ‘un-Islamic’, and from the US, which didn’t approve of Bhutto’s independence or his desire to go nuclear, to even the military officers who had been dismissed by him because they had expressed disagreement. Bhutto’s conceit and authoritarianism was central both to his achievements as well as to his downfall.

In July 1976, Bhutto made a key error by nationalising flour and rice husking mills, and cotton ginning factories. Not only had he gone back on his word of no more nationalisation, but this decision hit a core constituency of the middle and petit bourgeois classes that could have been allies of the PPP in the Punjab. This one single decision by Bhutto alienated them from his populist and progressive economic policies. These groups may have voted for Bhutto in 1970, but with their key economic interests threatened, they turned their back on him. That many of these individuals and groups belonged to the more socially conservative segments, only made them become a powerful tool in the hands of a strong political and social opposition that was largely Islamist and was looking for revenge.

The opportunity came in January 1977 when Bhutto announced early elections. There was little doubt that Bhutto would be re-elected, for there was little organised political opposition in place. No single party would have been able to oust Bhutto. However, a coalition of nine parties, many of which were Islamic parties, including the Jamaat-e-Islami, the Jamiat-e-Ulema-e-Islam, and the Jamiat-e-Ulema-e-Pakistan, formed a conservative and right-wing coalition titled the Pakistan National Alliance (PNA). The fact that the National Democratic Party led by Sherbaz Mazari and Begum Nasim Wali was also part of the PNA demands far greater analysis than simply labelling PNA as being an Islamist conspiracy. The PNA was a broad spectrum of left-leaning, centrist and rightist parties with their main focus on opposing Bhutto.

The PNA fought a campaign on the basis of an anti-Bhutto agenda, citing his ‘un-Islamic’ ways, and was helped by the newly alienated middle and petit bourgeois classes, especially in the Punjab. The results after the March 7 elections left the PPP with 155 seats and the PNA with 36. The equation surprised not only the opposition parties, but also the PPP, and, indeed, Bhutto himself. While the PPP would probably have retained government in the 200-strong National Assembly, such a massive victory margin suggested foul play. The PNA boycotted elections to the provincial assemblies and organised extensive street protests against the Bhutto government.

The PNA movement, as it is called, was clearly Pakistan’s most successful right-wing political movement, just as Bhutto’s 1968-69 movement was Pakistan’s most successful popular movement. Some scholars have made claims that the PNA was being funded through dollars coming from abroad; a claim which Bhutto indirectly referred to in his address to the National Assembly at the time.

The strong anti-Bhutto movement had acquired an Islamist hue from very early on, and, despite Bhutto making numerous symbolic concessions – such as banning alcohol, declaring Friday, instead of Sunday, as the weekly holiday – the PNA leaders were not going to ease their pressure on Bhutto.

Following sustained street protests, negotiations continued between March and July, and while there is now evidence that an agreement between the PNA and Bhutto had been reached around midnight July 3-4, Gen Zia, Bhutto’s hand-picked Chief of the Army Staff, in a military operation ironically called Fairplay, declared Martial Law on July 5, 1977, and deposed and imprisoned Zulfikar Ali Bhutto.

One cannot but emphasise the fact that General Zia’s coup and Martial Law was also encouraged by the practices and whims of some political leaders of the opposition. Retired Air Marshal Asghar Khan had written an open letter to the three services chiefs, including Zia, to rise up against Bhutto. The practice by opposition politicians inviting the military to remove an elected leader was to continue well into the 1990s, with some overtones as recently as 2014 during the famous dharna (sit-in) in Islamabad.

Moreover, as Shuja Nawaz has argued, evidence also emerged that some senior generals had established close links with the opposition parties. There seemed to be a clear common interest of those who financially backed the PNA movement, the generals who wanted a return to order and stability, and Islamist groups who felt that, with Bhutto out of the way, they would be closer to imposing some form of Islamic order in Pakistan.

Not just was Pakistan’s first democratically elected leader later executed in a trial which many believed was fixed from the start, in 1979, but Pakistan changed forever after July 5, 1977. Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah’s Pakistan and his vision died not so much on December 16, 1971, as they did on July 5, 1977.

LEGACY

The slogan which one hears now only infrequently, Zinda hai Bhutto, zinda hai, is as irrelevant to today’s Pakistan as is the attempt by some liberals to find and secure the Pakistan originally conceived and founded by the Quaid. Both ideals have been brushed aside by history’s changing tides in Pakistan.

Bhutto’s policies of social democracy, nationalisation, asserting working peoples’ consciousness and rights, his brand of ‘third worldism’, were all manifestations of a particular historical age. Now, neoliberalism and social conservatism tainted through a Saudi brush are the dominant cultural, social and economic forms of practice in today’s Pakistan, and, to some extent, globally.

Yet, in many ways, the issues of social justice, equality and sovereignty – themes that formulated Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s ideals for Pakistan – still remain relevant to our age where growing inequality, intolerance and militancy define where we have come since July 5, 1977. The fact that no politician today raises these issues is a sad reflection of how Bhutto’s ideals have been forgotten. Moreover, the fact that Zia’s legacy far outlives Bhutto’s also explains how much Pakistan has changed since 1977.

The writer is a political economist based in Karachi. He has a PhD in History from the University of Cambridge, and teaches at Columbia University in New York and at the IBA in Karachi.

https://www.dawn.com/news/1361239/special-report-democracy-in-disarray-1974-1977