The following are excerpts from an article under the same headline that was published in Dawn on December 25, 1976, as part of a supplement marking the Quaid-i-Azam’s birth centenary.

ALL those who knew Quaid-i-Azam intimately, know very well that he did never crack a joke merely for the sake of raising a laugh. He was too self-controlling and disciplined a man to waste time on little things. One thing he valued most was, Time. Time, he knew, can never return. Shakespeare said: “Oh! Call back yesterday / bid time return”. But Quaid-i-Azam never had the need to do so. He used every minute of his life as carefully as he wanted to. Punctuality, keeping appointments and never wasting a moment was his second nature.

He was [once] arguing an appeal before the full bench of Bombay High Court. He argued the whole day. The working time was up to 5pm. The judges asked: “Mr. Jinnah, how much more time would you need to finish your side?” He replied: “My Lord, hardly 15 minutes.”

Then the senior judge [on the bench] said: “Could you continue for a few minutes longer today and finish your address?” Normally, when a High Court judge says so, no lawyer would decline. But not so with Mohammad Ali Jinnah. “My Lord, I would love to do so, but I have a very important appointment which I can just make in time if I leave the court at once.”

The junior-most judge sitting on the left side of the chief justice whispered to him to insist that the case be finished on the day. “That is all right, Mr. Jinnah. We also have an appointment, but we like to finish this today so that judgment can be delivered on Monday.” Out came the reply from this great lawyer, shooting like a gun: “My Lords, the difference between your Lordships and myself is that (raising his voice) I keep my appointments.”

The three judges, Engilshmen, all went more red in their face than they already were. They all rose as if in a huff. Everybody got up and while the advocates bowed fully, the judges seemed only to nod. It was thought that the solicitor, who had instructed Jinnah, felt that this may affect the result of the case. The next morning the judges appeared in a very good mood.

Advocacy

Mr Jinnah was absolutely on the top of the profession. Therefore, naturally many lawyers tried their best to be allowed to work with Mohammad Ali Jinnah but very few could be taken. Mr. Frank Mores, then Editor of Indian Express, once wrote: “Watch him in the court room as he argues his case. Few lawyers can command a more attentive audience. No man is more adroit in presenting his case. If to achieve the maximum result with minimum effort is the hallmark of artistry, Mr. Jinnah is an artist in his craft. He likes to get down to the bare bones of his brief in stating the essentials of his case. His manner is masterly. The drab court rooms acquire an atmosphere as he speaks. Juniors crane their necks forward to follow every movement of his tall well-groomed figure. Senior counsel listen closely, the judge is all attention; such was the great status of this top lawyer.”

Once a very close friend whose request Mr. Jinnah could not decline came with his son who had just returned from England as a full-fledged barrister. He said: “Jinnah, please take my son in your chamber and make him a good lawyer.”

“Of course, yes,” said Jinnah. “He is welcomed to work in my chambers. I will teach him all I can. But I cannot transmit my brilliance to him”. Then slowly he added: “He must make his own brilliance.” This went into the heart of the young barrister and he worked so hard on the briefs and the law that one day he too became a great lawyer, but nowhere near the height of Mr. Jinnah.

People’s enthusiasm

It was around 1936-37 that Quaid-i-Azam came to Karachi and appeared before the Chief Court of Sind, as it then was, and appeared in a very important case and three lawyers of Karachi appeared against him. He had made a name as a lawyer long ago and in politics also he figured as a giant personality.

Consequently the rush to the court room consisting of lawyers, students and politicians was so great that the court room was full to the brim. The entrance to the court room had to be closed to stop any noise, so that judicial work could be carried on with a decorum and dignity befitting the occasion. But at the end of every hour, the door was ordered to be opened so that those who wanted to go out or come in could do so. When the first opening of the door at 12 O’clock occurred there was such a noise of rush that it appeared that the judges would lose their temper.

“My Lords,” said Jinnah in very sweet, melodious voice, “these are my admirers. Please do not mind. I hope you are not jealous.”

There was a beam of smile on the faces of judges and they appeared to be magnetically charmed by the words of the great persuasive man. The door remained opened and Quaid-i-Azam looked back on the crowd, raising his left hand indicating that he desired them to keep quiet. The atmosphere became absolute pin-drop silence as if by magic. The case proceeded for two days.

Quaid and students

The Quaid-i-Azam was fond of students. He loved them immensely. He always exhorted them to study hard. “Without education”, he said, “all is darkness. Seek the light of Education”. In particular, he was most attached to the Aligarh Muslim students. He used to visit the Aligarh University as often as he could. In fact, in his will, he left the entire residue of his property worth crores of rupees to be shared by the Aligarh University, Sind Madressah and Islamia College, Peshawar.

On one occasion at Aligarh after a hard day’s work of meeting people, addressing the students as he was sitting in a relaxed mood, he was told that one student, Mohammad Noman, was a very fine artist of mimicry. He could impersonate and talk or make a speech with all the mannerism of his subject. Quaid-i-Azam was told that this student could impersonate him to such a degree that if heard with closed eyes, Quaid-i-Azam will think that it was he himself who was speaking and he will think as if he himself was talking to Quaid-i-Azam.

Quaid-i-Azam sent for the student at once. The student asked for 10 minutes’ time to prepare himself. After 10 minutes the student turned up dressed in dark gray Sherwani, a Jinnah cap and a monocle, like Quaid-i-Azam. Of course, he could not look like Quaid-i-Azam, but the appearance on the whole was somewhat similar.

Then the student put on his monocle and addressed an imaginary audience. The voice, the words, the gestures, the look on his face and everything appeared like Quaid-i-Azam. In fact, if he had spoken behind a screen without being seen, the audience would have taken him to be Quaid-i-Azam speaking himself. Quaid-i-Azam was very much pleased with the performance. But when it was finished, the culmination came unexpectedly. Quaid-i-Azam took off his own cap and monocle and presented to the student, saying: “Now this will make it absolutely authentic.”

Purdah

In November, 1947, Quaid-i-Azam was in Lahore and he personally supervised operation of the rehabilitation of refugees. One day Quaid-i-Azam was invited to a girls college. The girls and ladies of the staff did not observe purdah as he addressed them.

When back at Government House, Quaid-i-Azam was in a humorous mood and wanted to know why the ladies did not observe purdah. His sister, Miss Fatima Jinnah, said: “That was because they regarded you as an old man.”

“That is not a compliment to me,” said Quaid-i-Azam. Liaquat Ali Khan, who was present, said: “That was because they regarded you as a father”.

“Yes, that makes some sense.”

Man of character

Quaid-i-Azam was a man of such a strong character that he could not be easily attracted toward anyone, including women. Excepting his wife, there is no instance whatsoever of anyone at whom he glanced in love.

Once in Bombay, where he had gone to an English club to relax after hard day’s work, he played cards. The game was called Forfeit. It was played among four persons – two gentlemen and two ladies. Tradition required that the lady who lost the game must offer to be kissed by the gentlemen who won. The lady indeed was very attractive and she offered Quaid-i-Azam to be kissed by him.

Quaid-i-Azam said: “My lady, I waived my rights. I cannot kiss a lady unless I fall in love with her.”

Rose between thorns

On the 14th day of August, 1947, Lord Mountbatten with his wife came to Karachi for the investiture ceremony of the Governor-General of Pakistan. After Quaid-i-Azam was sworn in, the new State of Pakistan was handed over to him legally, constitutionally and with proper ceremony.

Lord Mountbatten proposed that Quiad-i-Azam be photographed with Lord and Lady Mountbatten. Quaid took it for granted, that, as usual etiquette requires, the lady will stand between the gentlemen. So he told Lady Mountbatten: “Now you will be photographed as the rose between the two thorns”. But Mountbatten insisted that Jinnah should stand in the middle. He said that being a Governor-General etiquette requires that Quaid-i-Azam should be in the centre. Naturally, Quaid-i-Azam yielded.

And when Quaid-i-Azam stood between the two, Mountbatten said to him: “Now you are the rose between two thorns.” He was right.

Whenever Quaid-i-Azam was cornered in a difficult situation, he proved greater than his opponent. His political enemies always wanted to publicise that Quaid-i-Azam was always with the Congress, but when the opportunity came he switched over to Muslim League.

In December, 1940, Quaid-i-Azam visited London along with the Viceroy and Congress leaders. He furnished details about Pakistan issue and quoted facts and figures as to how the Congress had betrayed the trust of the Muslims. One correspondent said to him: “Oh, you were also in the Congress once.” Jinnah retorted: “Oh, my dear friend, at one time I was in a primary school as well!”

Trick countered

In 1946, political agitation both by Congress and Muslim League had reached its zenith. The British government, always master of the art of side-tracking the main issue, suggested to Jawaharlal Nehru that as very soon India will be handed over to them, so as a beginning some Hindus and some Muslims should be taken in the Interim Cabinet. Before that there was no such thing. The body which was functioning was the Viceroy’s Executive Council. But Jawaharlal Nehru insisted that it should be called a Cabinet. Example was shown that the Viceroy himself calls it a Cabinet.

Quaid-i-Azam refused to do so. He said the Cabinet is a constitutional body the members of which are selected from the members of Parliament by the leader of majority. Here, there is no such thing. It is purely an Executive Council and it cannot become a Cabinet merely because you call it a Cabinet. A donkey does not become an elephant because you call it an elephant.

Call for honesty

Gandhi always used to speak about his inner voice. He seemed to create an impression that there is something spiritual within him, which, in time of necessity, gives him guidance and he obeys it and calls it his inner voice. As a matter of fact Gandhi often changed his opinion and suddenly took the opposite stand. Quaid-i-Azam called it a somersault.

Once having committed himself to a certain point of view, he took a dramatically opposite stance. On the next day, Gandhi maintained that his inner voice dictated him to take the opposite view. Quaid-i-Azam lost his temper and shouted: “To hell with this Inner Voice. Why can’t he be honest and admit that he had made a mistake.”

In June 1947, partition was announced by Lord Mountbatten. He insisted on an immediate acceptance of the plan. Quaid-i-Azam said he was not competent to convey acceptance of his own accord and that he had to consult his Working Committee. The Viceroy said that if such was his attitude, the Congress would refuse acceptance and Muslim League would lose its Pakistan. Quaid-i-Azam shrugged his shoulders and said: “What must be, must be.”

In July 1948, Mr. M. A. H. Ispahani went to Ziarat where Quaid-i-Azam was seriously ill. He pleaded with Quaid-i-Azam that he should take complete rest as his life was most precious. Quaid-i-Azam smiled and said: “My boy there was a time when soon after partition and until 1948, I was worried whether Pakistan would survive. Many unexpected and terrible shocks were administered by India soon after we parted company with them. But we pulled through and nothing will ever worry us so much again.

“I have no worries now. Men may come and men may go. But Pakistan is truly and firmly established and will go on with Allah’s grace forever”.

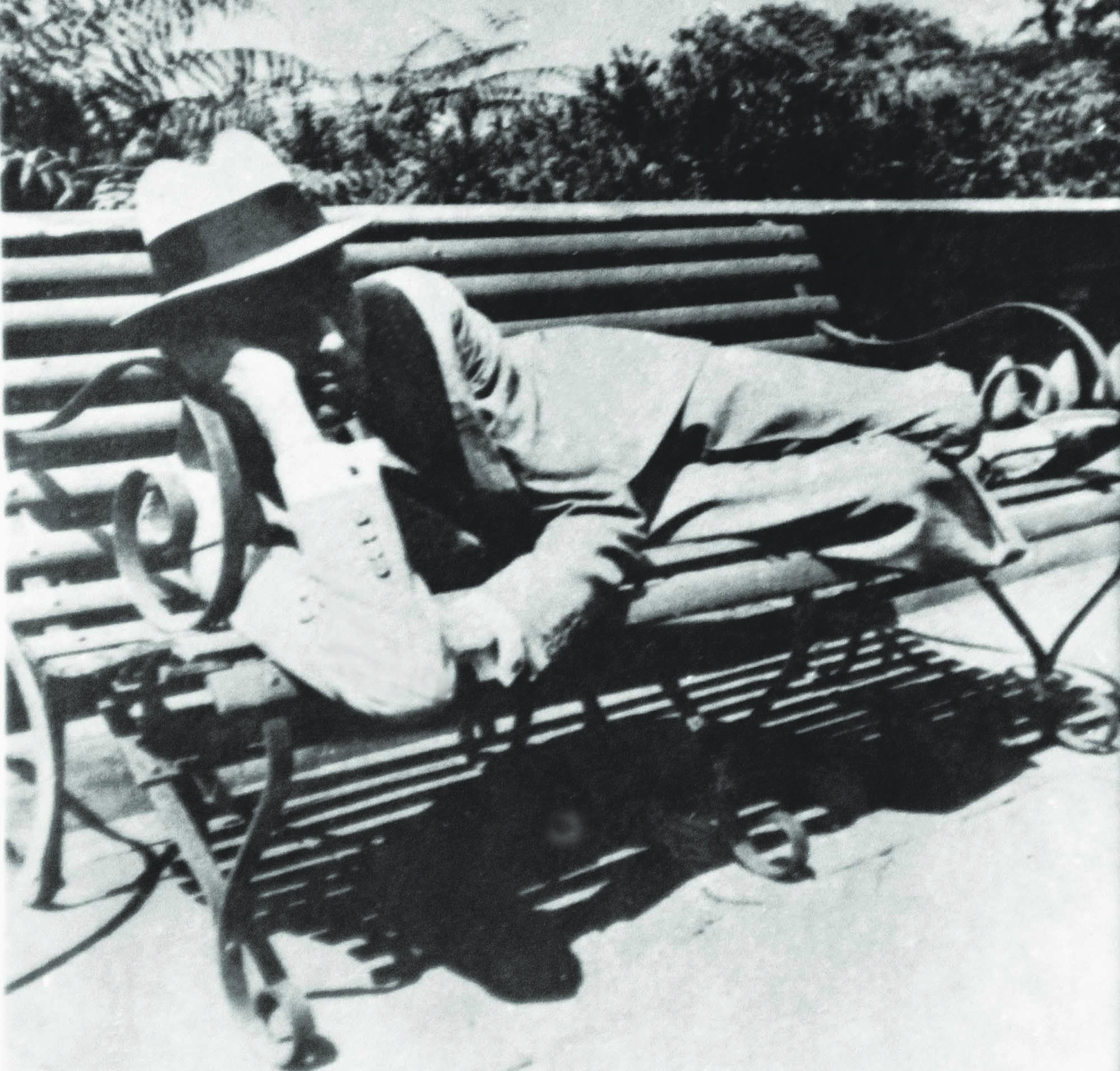

![Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah and Miss Fatima Jinnah enjoying a boat ride, possibly in Dhaka, in the early 1940s. Standing on the left [wearing sherwani] is Khawaja Nazimuddin, who was at the time the Premier of Bengal. | Photo: The Press Information Department, Ministry of Information, Broadcasting & National Heritage, Islamabad (PID)](https://i.dawn.com/primary/2017/09/59b3d7602302f.jpg)