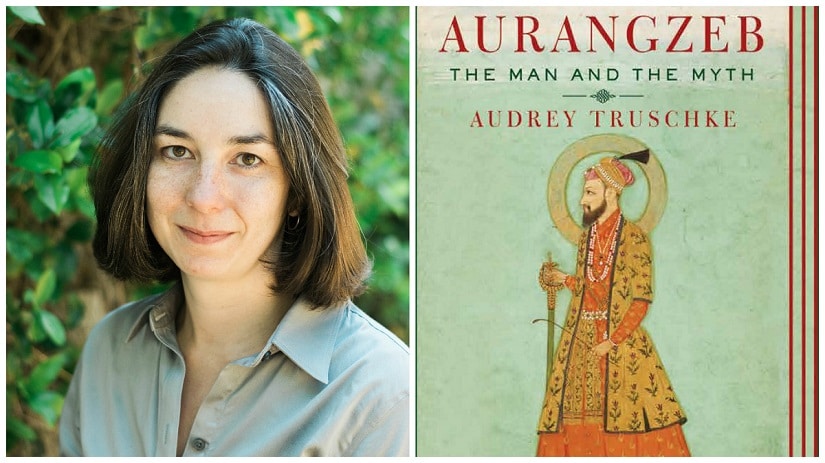

Scrolling through Audrey Truschke’s Twitter timeline is somewhat exhausting. The assistant professor of South Asian History at Rutgers University-Newark has been at the receiving end of a social media backlash ever since her book — Aurangzeb: The Man and The Myth — was published earlier this year. Truschke, however, seems unfazed, and responds to nearly every point that is addressed to her regarding her tome.

Truschke studied Sanskrit and majored in Religious Studies at the University of Chicago, before pursuing a PhD at the Department of Middle Eastern, South Asian, and African Studies at Columbia University. Her research focuses on early modern India, especially the Mughal period and cross-cultural interactions therein.

Before Aurangzeb, she authored Culture of Encounters: Sanskrit at the Mughal Court (2016).

In an email interview with Firstpost, Truschke spoke about the row over her book:

Did you expect quite the backlash there’s been to Aurangzeb? The response to your remarks in The Hindu in 2015 must have given some indication…

I expected a backlash to Aurangzeb. But I didn’t write it for my critics, especially those who dismiss the book on the basis of reviews or simply the subject matter. Rather, I wrote Aurangzeb because I thought that there was a hunger among some in India for a more balanced, historically-based view of Aurangzeb. I have been heartened to hear from a number of readers who have substantive questions about my arguments in the book and desire to learn more about one of the most crucial political figures of early modern India.

You said in an interview that it was the response to The Hindu piece that had prompted you to start working on Aurangzeb… what particularly was the exchange that convinced you this was a project you needed to engage with?

People wrote letters to the editor for days after I gave (the) interview to The Hindu in 2015. I did not even know that one could write letters to the editor regarding an interview. The sustained response to my brief comments on Aurangzeb prompted me to see an opportunity to provide interested readers with a more nuanced, compelling story regarding this crucial king.

What are the common themes you’ve observed in the stories about Aurangzeb that are in popular circulation?

The strongest thread in popular stories about Aurangzeb is anti-Muslim sentiments. People repeatedly reduce everything that Aurangzeb did to his piety — as they imagine his piety anyway — and then condemn him as too Muslim. Such arguments have little to do with Aurangzeb but a great deal to do with current biases against Muslims in India.

What’s been the hardest myth about Aurangzeb to debunk, for you as a historian?

The most difficult point for me to get across is that I am not asking the question of whether Aurangzeb was a good or bad guy. Many of my critics have trouble seeing beyond the dichotomy that he must have been a sinner or a saint. I do not want to judge Aurangzeb by modern standards because that tells us nothing interesting about the emperor or his world. But many people have trouble wrapping their heads about the concept of asking questions about a historical figure other than — was he a villain or a hero.

Does it ever get to you, responding to the unending stream of criticism on Twitter?

I have rather thick skin, which serves me well in dealing with public criticism and hate speech. However, many of my colleagues in the academy do not share my stomach for hostility. The vicious atmosphere on social media drives many scholars away from public engagement, which is to the detriment of everyone, in my view.

One of the reviews for Aurangzeb stated, “In fact, one suspects she first decided to humanise, secularise Aurangzeb and then went about finding documents supporting it”. Do you find criticisms like that trying, as an academic?

I find such criticisms flimsy. This particular argument insinuates a dishonest process of researching and writing on my part but fails to provide any evidence for the claim. As a historian, I am far more interested in substantive arguments.

(Among the rebuttals to Aurangzeb), is this blog post that has received some amount of attention. What is your opinion of it?

To me, blog posts such as this exemplify the need for historians to continue educating an interested public about what constitutes a compelling historical argument and good-faith use of historical evidence.

You’ve said in a previous interview: “The past is rarely, if ever, only about the past. But when we allow modern interests to constrain and dictate our view of the past, then we are engaging in mythology that, however powerful, is not history.” In the post-truth, ‘fake news’ era, how do you see the role of the academic?

Our approach to the past is always preceded by and conditioned by the present. That is as true for me as it is for those who wish to rewrite India’s past. The difference is that I remain committed to dispassionate history, meaning an honest attempt to recover the past and understand historical figures and events on their own terms. One challenge going forward, for historians, is to better articulate why the historical project holds value and why it is a mistake to treat the past as a blank canvas upon which we can write present-day concerns.